Home » Second World War (Page 2)

Category Archives: Second World War

Rifleman Albert Leddy, 1924 – 2021

We have just received the sad news of the death of Rifleman Albert Leddy who served in Italy and Austria with G Coy, 2nd Battalion London Irish Rifles before becoming a piper with the 1st Battalion in Italy.

Albert had written a little bit about his life in Liverpool prior to being called up:

“When I left school at the age of 14, I started work as a chandler’s boy going out with a horse and covered wagon selling soaps and washing powder and other cleaning materials in and around Liverpool. Then I went to work in a stable for a haulage firm near to Liverpool docks, then later I was sent to another stable to take out a pony and trap used for carrying small loads or the odd bale of cotton. I later went back to the other stable to work with a one-horse wagon working around Liverpool docks and railways. I finished working for them and went to work for a shipping butcher in Old Hall Street and supplied many of the big ships that came into Liverpool docks with meat, veg and fish.

In October 1942, when I turned eighteen, I received my calling up papers for military service…”

When Albert was called up, he was initially posted to the Royal Artillery before transferring to the Faughs in 1943 and then sent out to Italy to join the Irish Brigade as part of a reinforcement draft. He transferred with 2 LIR in the front line in April 1944 just before the final Cassino battles. From the Liri Valley, he journeyed with the London Irish to Trasimeno, Rome and Egypt, returning to Italy in September 1944 for the Gothic Line winter battles, manning the Senio riverbanks and joining the final Kangaroo Army advance through the Argenta Gap up to the river Po in April 1945.

After seven months of rest in Austria, in early 1946, he transferred to 1 LIR, who were then based near Trieste and, there, he learnt to play the pipes. Piper Albert Leddy was de-mobbed from Italy in 1947.

His son, David Leddy, wrote to us to tell us more about his father:

“He was still playing the pipes as late as the last New Year (2020/21) to his fellow residents at his care home. He was really pleased with the pipers’ cap badge that the LIR sent to him and wore it with pride. My grandfather was a coal merchant in Liverpool just before the war and I understand that my father was his pony wagon driver, assisting him to deliver coal. After the war, my father moved to Warwick to live with his brother (Ted) and went to work in the motor industry. At first, he worked at the Ford Foundry in Leamington Spa for a short period, then moved to Coventry to join the Standard Motor Company producing cars. He moved back to Ford and later went again to work for the Standard Motor Company where he stayed for 21 years and, there, joined the works band, the Standard Triumph Pipe Band, with whom he played for many years.”

Albert was 97 years of age. A full, long life indeed !!

Quis Separabit

Faugh a Ballagh !

The London Irish Rifleman who walked to freedom

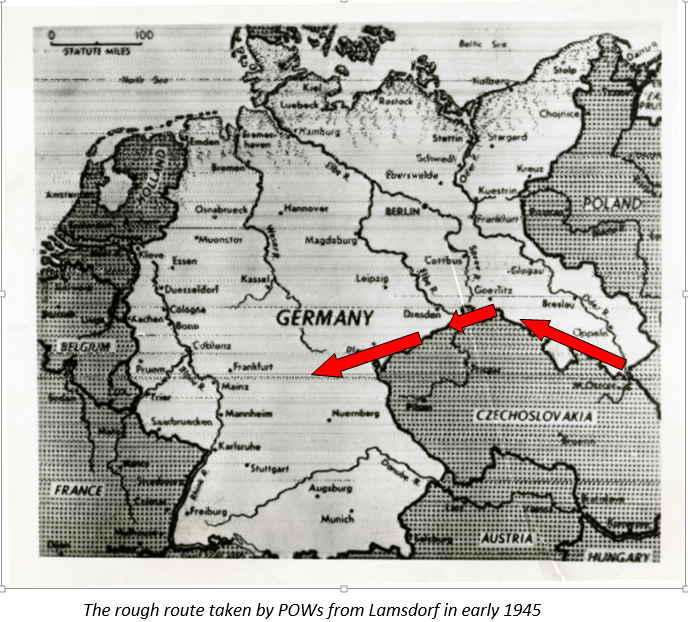

January and February of 1945 were among the coldest winter months recorded in Europe in the entire 20th century. In Silesia, then part of the Third Reich but now in Poland, temperatures fell to 25 degrees centigrade below freezing.

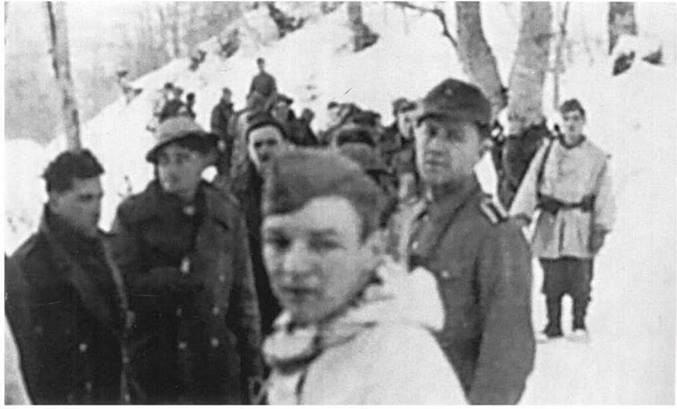

These were the conditions that faced Prisoners of War (POWs) at the Stalag VIII camp near Lamsdorf (now Gmina Lambinovice) when they were ordered to march west before the huge Soviet offensive that commenced in early 1945. Most of the POWs had been weakened by years of bad food. None had suitable clothes and they were now ordered to walk up to 25 miles a day. The evacuation was part of a massive movement from camps including the Auschwitz extermination camp in the path of the Red Army steamroller. It was a formula for suffering and death.

Around 80,000 men from Stalag VIII and other POW camps were driven west. They included David Moore, a native of Airdrie in Lanarkshire, who had been enlisted into The Cameronians in January 1940 before being transferred to the London Irish Rifles at the end of 1942, not long after he got married.

Moore had been dispatched to join the 2nd Battalion London Irish Rifles in North Africa at the end of November 1942 and was involved in the battalion’s battles in Tunisia, Sicily and along the Adriatic coast. In March 1943, he had been promoted to Lance-Corporal.

L/Cpl Moore was a section leader with No 7 Platoon, E Company when they were posted in January 1944 to a patrol outpost north-west of the village of Montenero in the upper reaches of the Sangro river valley. The battalion’s role was to watch for patrols from a German Mountain Regiment, which were harassing the Allied front line in the Abruzzi mountains 40 miles east of Cassino .

Lacking winter equipment and camouflage, E Company had been camping out for several days in deep snow drifts on Il Calvario, a high point more than 3,000-feet above sea-level. On the morning of 19 January after another freezing night, Moore was attending an ‘O’ Group with other section leaders in the tent of 7 Platoon commander, Lieutenant Nicholas Mosley, when German ski borne troops attacked. A mortar shell hit a tree about a foot from the door of the tent, injuring a couple men including Moore who suffered wound to his arms and head. Mosley ordered the riflemen into their trenches and to prepare to put up resistance, but they were quickly surrounded, Five London Irishmen had been killed in the short battle.

Most of 7 Platoon were taken prisoner including Lt Mosley himself, though he and three others managed to escape their captors as a result of a partially successful rescue by E Company’s reserve platoon and led by Company Commander, Major Mervyn Davies. David Moore and 19 of his comrades, some without boots, were marched under armed guard through deep snow into the mountains north of the Allied lines and he was then treated for his wounds at a hospital in Florence. At one point, when he awoke and saw the distinctive uniform of the nurses, Moore had thought that he had “died and gone to heaven”.

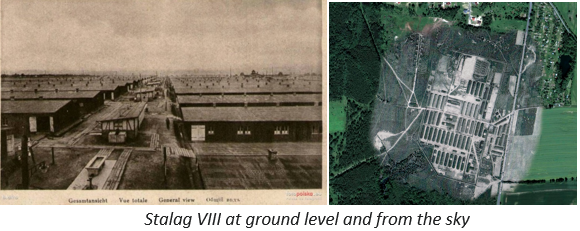

From Italy he was shipped by train to an enormous complex of POW camps in Silesia. His destination was Stalag VIII-B in Lamsdorf, which was also known as Stalag-344. The camp was originally built for no more than 15,000 but, by the end of 1944, it held an estimated 49,000 men, including more than 3,000 Allied prisoners. The military hospital and the infirmary of the camp were always overcrowded. Inspectors from the Red Cross criticised the poor conditions of the clothes of most prisoners and the lack of medication in the military hospital. In winter, the barracks were barely heated and, by 1944, there was a lack of water. Russian and Italian prisoners would be denied all medical assistance.

“(It was a) time he didn’t say very much about,” his son David Moore says. “On his release he said that his treatment had been reasonable though food was in short supply. Red Cross parcels helped to keep him alive.”

This was to change for the worse when the camp was evacuated in February 1945 when POWs were marched out in groups of around 200 into an arctic landscape. The Germans provided farm wagons for those unable to walk and teams of POWs often pulled the wagons through the snow because of the lack of horses. The reception was mixed in the German villages that they passed through on their journey west. There was occasional hostility and rocks were thrown by people angry about Allied bombing while on other occasions, penniless people shared whatever little food they had. At night, those with intact boots who risked taking their boots off to avoid trench foot found they couldn’t get their swollen feet back into them in the morning. Boots froze and were sometimes stolen. There was almost no food and the men had to scavenge, eating rats and cats to fend off starvation. Dysentery and frostbite were common and there were cases of typhus, which was spread by body lice. Some men died of exposure while they slept.

As the weather slowly improved in March, the widespread thaw turned roads into a quagmire of mud. Many POWs marched more than 300 miles before they reached Allied armies advancing into south-west Germany. Up to 3,500 British, Commonwealth and American POWs are estimated to have died in what is known as “The Death March.”

“It was a nightmare experience for my father,” his son says. “He spent the next ten weeks walking between 15 and 30 kilometres most days until he was finally released by Allied soldiers and repatriated to the UK. He suffered all the privations recounted by many who took part in and survived this horrendous experience including bitter cold and extreme hunger. I recall him speaking about it only when he recounted the kindness that he and a pal were shown by a German woman who cooked them a good meal when they arrived at her door with only a handful of rice and had asked her to boil it up for them. By the time he got home, he was suffering from flat feet, damaged ankles and metatarsalgia as a result of prolonged standing.”

After recovering his health, David Moore was transferred to the RASC where he remained until he was released to Army Reserve in May 1946. He then returned home to his wife Sadie in Scotland and they would have two children, three grandchildren and two great grandchildren who knew him, plus two others who were born after David’s death, at the age of 92, in January 2009.

A most remarkable story of human resilience.

A memorial was later erected on the site of Stalag VIII in memory of the thousands who died there and during “The Death March”.

The inscription on the sandstone plate next to the memorial reads: Stalag VIII: A place sanctified by the blood and martyrdom of the prisoners of war of the anti-Hitler coalition during the Second World War.

Lance Corporal David Moore

David Moore has written to us about his father, Lance Corporal David Moore, who served with the London Irish Rifles during the Second World War:

“My father was born on 18th February 1917 in Airdrie. His Army number was 3249725 and he served in the Cameronians before joining the LIR and then joined the RASC when he returned from POW camp in June 1945 until he received his release papers on 17th February 1946.

Somewhere in Italy, Xmas Day 1943.

My father served in the 2nd Battalion, London Irish Rifles from 26th November 1942 until 13th June 1945. During this time, he was in Tunisia and Italy but was wounded and taken prisoner in January 1944. He was eventually sent to Lamsdorff POW camp and, in 1945, was forced to take part in “The Long March” across Europe. He survived this horrendous journey but, as with many old soldiers, my father wouldn’t talk about his experiences in later life – something I now very much regret especially as I spent my working life as an historian.

I received his Army records recently and these helped greatly in clarifying some details of his time with 2 LIR. He was indeed transferred to the Battalion on 26.11.42 and, according to his records, he fought in North Africa from December 1942 until the fall of Tunis in May 1943. It may be of interest to you that he was in E Company and was promoted to Lance Corporal in April 1943.

My father was subsequently sent to Sicily and you are very familiar with E Company’s movements there – then onto mainland Italy. He was with the 2nd Battalion all the way up the Adriatic coast and then was at Campobasso at Christmas 1943. Unfortunately, he was in 7 Platoon, under the command of Nicholas Mosley, on the morning of 19th January 1944 at Montenero Val Cocchiara when his platoon was overrun – he was with Mosley at his tent when a shell exploded nearby and was wounded in the side of the head and arm. Sergeant Sale was tending my father’s wounds when they were surrounded and captured.

My father is specifically mentioned twice by Mosley in his account of the event – firstly, his wounding and secondly, when he was a prisoner being led away by his captors. His army records note that he was taken prisoner at “Alvadene” but this is not correct, though I suspect that he was taken from the mountains near Montenero to Alfedena down in the valley. My only recollection of my father’s account of this episode is how angry he was at Mosley but I can only speculate as to the reasons. In one report I read, it suggested that, after Mosley was freed by Major Mervyn Davies, he would return to Montenero to face some “awkward questions”.

Further details of the German raid at Montenero are given below:

In the grip of an Italian winter high in the Apennines, 2 LIR were in the Castel de Sangro area where they took up defensive positions in blizzard conditions on New Year’s Eve. The nights were long, daylight was in short supply in the middle of winter and the weather was atrocious as they were high in the mountains and suffering freezing conditions.

In January 1944, he was a Lance Corporal in 7 Platoon of E Company of the 2nd Battalion London Irish Rifles with each company taking turns on the front line in exposed forward positions on a mountainside opposite the German line near the small town of Montenero Val Cocchiara.

There was some shelling on the night of 18th January – the prelude to the dramatic events of the following morning. The Germans had fired shells towards the positions held by 7 and 9 platoons so it appeared that they knew the soldiers were there and a dawn raid was anticipated but did not materialise and perhaps the soldiers dropped their guard. At 08.30, while L/Cpl Moore was with the Section Commanders at Lieutenant Nicholas Mosley’s tent receiving orders for the day, a shell exploded in or near the tent and all of the Section Commanders were wounded.

According to Lieutenant Mosley’s account:

“At Calvario on the 19th January at 08.30hrs a Platoon ‘O’ Group was assembled to receive orders in the Platoon HQ tent when a shell hit a tree about a yard from the door of the tent…. I immediately ordered the platoon into their trenches….. In the next trench Sgt Sale, himself wounded in the wrist, was trying to bandage L/Cpl Moore who was bleeding from the side of the head and the arm.”

By the time Mosley got out of the tent, the entire platoon had been surrounded and was being disarmed by the Germans. They had materialised out of the woods wearing white smocks armed with machine guns, grenades and with bayonets fixed. The men of 7 Platoon had no chance and surrendered rather than be killed. Lieutenant Mosley saw L/Cpl Moore and Sgt Sale being led away by the Germans as prisoners but escaped himself.

L/Cpl Moore was transferred from Alfedena to Florence where he spent a month in hospital having his wounds attended to. When he awakened on arrival, he thought that “he had died and gone to heaven” when he saw the nuns all dressed in their white uniforms and wimpoles. That period in “heaven” didn’t last long as he was then moved to the POW camp, Stalag 344, at Lamsdorff in Poland.

From February 1944 to January 1945: A Prisoner of War in Poland – a time my father didn’t say very much about. On his release, he said that his treatment had been reasonable, although food was in short supply. Red Cross parcels helped to keep him alive.

21st January to 2nd April 1945: Everyone was ordered to leave the camp and to begin what became “The Long March” west away from advancing Russian troops. L/Cpl Moore and the other men spent the next ten weeks walking between fifteen and thirty kilometres most days until he was finally released by Allied soldiers and repatriated to the UK. He suffered all the privations recounted by many who took part in and survived this horrendous experience including bitter cold and extreme hunger. I recall my father speaking about it only once, recalling the kindness he and a pal were shown by a German woman who cooked them a good meal when they had arrived with only a handful of rice they had asked her to boil up for them. By the time he got home, he was suffering from flat feet, damaged ankles and metatarsalgia as a result of prolonged standing.

14th June 1945: As a result of his injuries, my father was transferred to the RASC, where he remained until he was released to the Royal Army Reserve on 13th May 1946.

For his war service, L/Cpl Moore was awarded The 1939-45 Star, The Africa Star, The Italy Star, The War Medal 1939-45 and the Defence Medal.

1946 to 2009: David was happily married to Sadie, who he had married in 1942, just before he joined the London Irish Rifles and they were together for just over 66 years. They had two children, three grandchildren and two great grandchildren who knew him, and three further great grandchildren born since his death in Airdrie on 9th January 2009.”

A remarkable long life and cetainly well lived.

Quis Separabit.

RJ Prentice 2 LIR

We received a note and some photos from Colin Prentice, the son of Robert John Prentice who served with the 2nd Bn London Irish Rifles during the Second World War – he is seen below (directly behind Lt Searles) on guard duty with H Company for General Montgomery at Vasto in December 1943 as he prepared to leave 8th Army.

In his note, Colin told us:

“I remember Dad telling me he was in the London Irish Rifles and then later served with the REME.

My Dad was in the Territorial Army at Girdwood Barracks on the Antrim Road in Belfast and worked at Gallaher’s tobacco factory for over 23 years. When he retired he worked at the police authority in Belfast as security next to the Royal Ulster Rifles Museum in Waring Street.

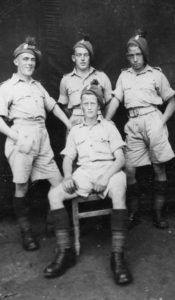

I have enclosed a few photos of him, one with his two brothers who were killed in action in Burma.

Below, my dad is in the middle with brothers Alfred, left and David, right.

My Dad is top left below in the boxing team

Below, my Dad on the right with his men on exercise, with the REME I think,

I also remember my father telling me that he was a boy soldier.

He did get wounded himself in battle being shot in the shin and then was hit in the other leg – with a “dum dum” I think he called it. He was then injured in the head and had to have a silver plate inserted and I remember him telling me that the doctor said he might not last long but my Dad lived until he was 73.

At his funeral service in 1996, his army comrades – Joe Farrell at the front and Billy McCullough at the rear – would flank his coffin “

Quis Separabit

Brothers in Arms – Riflemen William Jenkins and John Wilson

We have been contacted by David Jenkins, the nephew of William Jenkins who served with the 2nd Battalion (2 LIR) in Tunisia and Italy during the Second World War. In a moving note, David told us:

“I have been meaning to contact you for a while now in relation to my uncle, Rifleman William Norman Jenkins, No. 7020240 and his friend Rifleman John Slater Wilson, No. 7023037, who were both killed by the same German shell at Termoli on 6th October 1943.

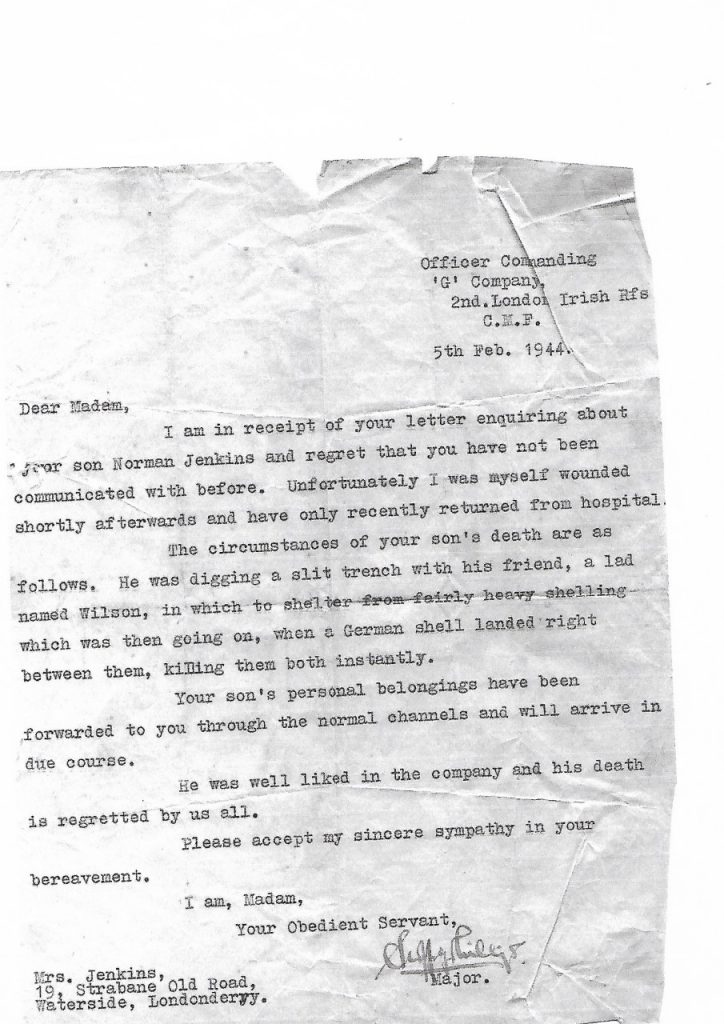

Major Phillips from G Company sent a letter dated 5th February 1944, to my grandmother detailing how William and his friend John were killed. Here are extracts taken from that letter:

Unfortunately I was myself wounded shortly afterwards and have only recently returned from hospital. The circumstances of your son’s death are as follows – he was digging a slit trench with his friend, a lad named Wilson, in which to shelter from fairly heavy shelling which was going on, when a German shell landed right between them, killing them both instantly. He was well liked in the company and his death is regretted by all of us.

William’s remains were then taken for burial to the Public Garden off Main Street near the Central Cemetery in Termoli. At a later date, he was then removed for burial to Sangro River Military Cemetery where he and John Wilson are buried beside each other.

William Jenkins was born in Londonderry on 3rd December 1919 and had two brothers and three sisters. His father, Samuel Jenkins, was one of eight brothers who had fought during the Great War. Samuel had served with the 6th Inniskillings at Gallipoli and Salonika where he came down with malaria but would recover and go onto serve with the Labour Corps in France. During the Second World War, he served in the Royal Fusiliers with the BEF in France and was rescued off the French coast 10 days after the last man had been lifted off Dunkirk. Following this, he served with the Queens Own West Kent Regiment Home Guard in Kent. In July 1941, Samuel and his company were billeted in a castle when he got up during the middle of the night, opened a cellar door and fell down a flight of stone steps. He was taken to hospital with concussion but died of his injuries the following day.

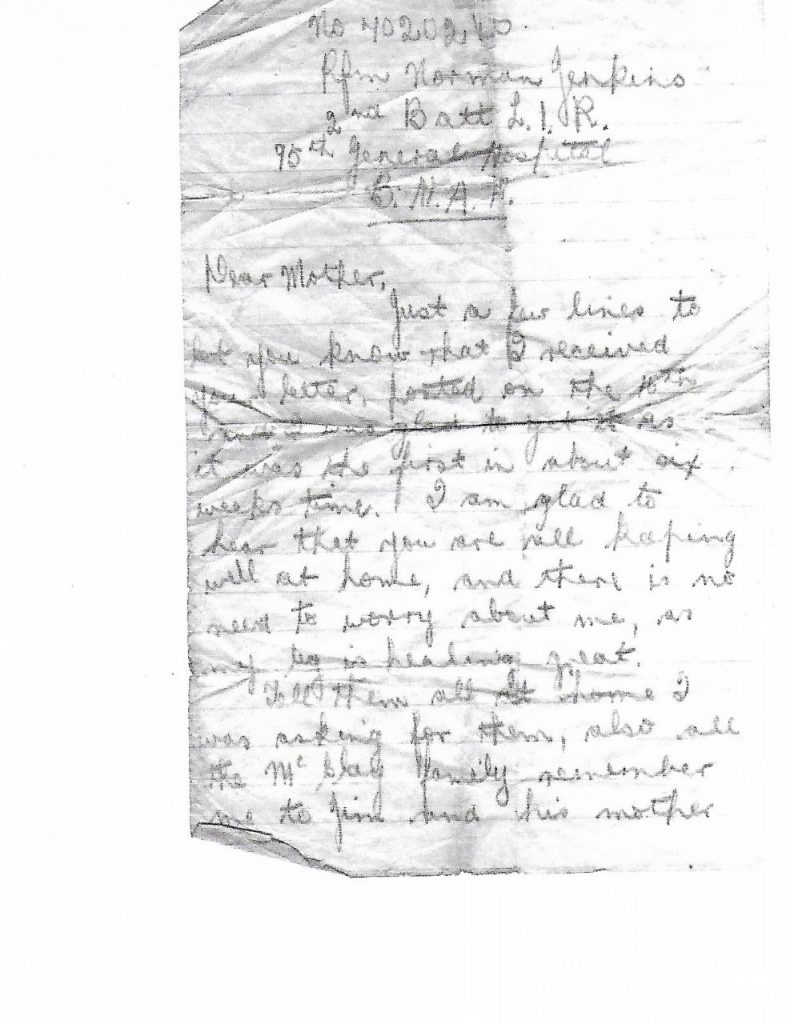

By then, William had joined the 7th Bn Royal Ulster Rifles – on 21st October 1940 in Londonderry, where he had been an Apprentice Baker. His records state that he was posted to 2 LIR on 29th August 1942 when they were located at Cumnock in Ayrshire. The records state that he embarked from Glasgow on 11th November 1942 and disembarked at Algiers on the 22nd. On 19th April 1943, when the battalion were positioned north of Medjez-el-Bab in Tunisia, William suffered a wound to his left thigh and was taken to the 95th General Hospital B.N.A.F., where he wrote a letter home stating that ‘there was no need to worry as his leg was healing well’.

He was discharged from hospital on 2nd August 1943 and joined up with the 2 LIR again on 6th September 1943 in Sicily before they departed for the mainland of Italy. Sadly, my uncle would be killed exactly a month later during the battalion’s fighting defence of the Termoli perimeter .

I have been looking for information about William’s friend, John Wilson, for over ten years now and it was only recently that I had a breakthrough. I was searching through newspaper archives and found John mentioned in a Manchester newspaper dated November 1944. He seems to have come from Wythenshawe and was recorded as being with the LIR but for whatever reason the article stated he was said to be missing. There is also a picture of him in uniform.”

We are most grateful to David Jenkins for sharing his family’s story.

Quis Sepaabit

Major Desmond Woods, 2 LIR

We were delighted to have been contacted recently by Adrian Woods, the son of Major Desmond Woods, who served with the 2nd Battalion as Officer Commanding of H Company from October 1943 to June 1944 until he was wounded in the fighting near Lake Trasimene in central Italy.

As well as his note to us, Adrian also passed over some additional extensive written details of his father’s service with the London Irish Rifles that had been transcribed from an interview by military historian, Richard Doherty – it’s a most remarkable story indeed and these details will be filed in the Museum’s archives.

During his 8 months with the London Irish Rifles, Major Woods was present during some of the most momentous battle periods for the 2nd Battalion – at the Sangro river, near Monte Cassino and at Sanfatucchio to the west of Trasimene.

During the assault on Casa Sinagoga on 16th May 1944 , H Company formed the centre of the battalion’s advance which ultimately broke through the vaunted Gustav Line in the Liri Valley and it was here that Major Woods was awarded a bar to the Military Cross that he had received before the war – at the same time, he would unsuccessfully recommend Corporal Jimmy Barnes for a posthumous Victoria Cross for his part in that day of most bitter fighting for 2 LIR.

After being wounded and medically downgraded, Desmond Woods became a Training Major for the Italian Gruppi Cremona in northern Italy before undertaking a distinguished post war service overseas with the Royal Ulster Rifles and later with other units in Northern Ireland.

Quis Separabit.

Rifleman Thomas Hatton

On Loos Sunday, we were delighted to meet the son and grandson of Rifleman Thomas Charles Hatton, who served with the 1st Battalion in the UK from April 1940 to June 1942.

His son, also named Tom, explained to us that soon after joining up, his father was based in Kent where the battalion was helping the return of the Dunkirk evacuees. After this, they would continue to be positioned in the south east of England during the Battle of Britain period and then spent time at Bognor Regis before the London Irish Rifles moved onto Essex in 1942. It was during this latter period that Rifleman Hatton was seriously injured in a training accident that led him to be formally discharged from army service on 4th June, a few months before the 1st Battalion were to go overseas to the Middle East.

After returning to his wife Daisy and baby son in south London and, despite the effects of his war time injuries, Tom was able to live a very long and eventful life well into his 90s.

During the visit to Connaught House, Tom Hatton jnr shared a few photos and details of his father’s war time service with us.

It was marvellous to learn more about Rifleman Tom Hatton’s war time service and meet his son and grandson who, perhaps unsurprisingly, is also called Tom !

Quis Separabit.

The London Irish Rifles in Piedimonte

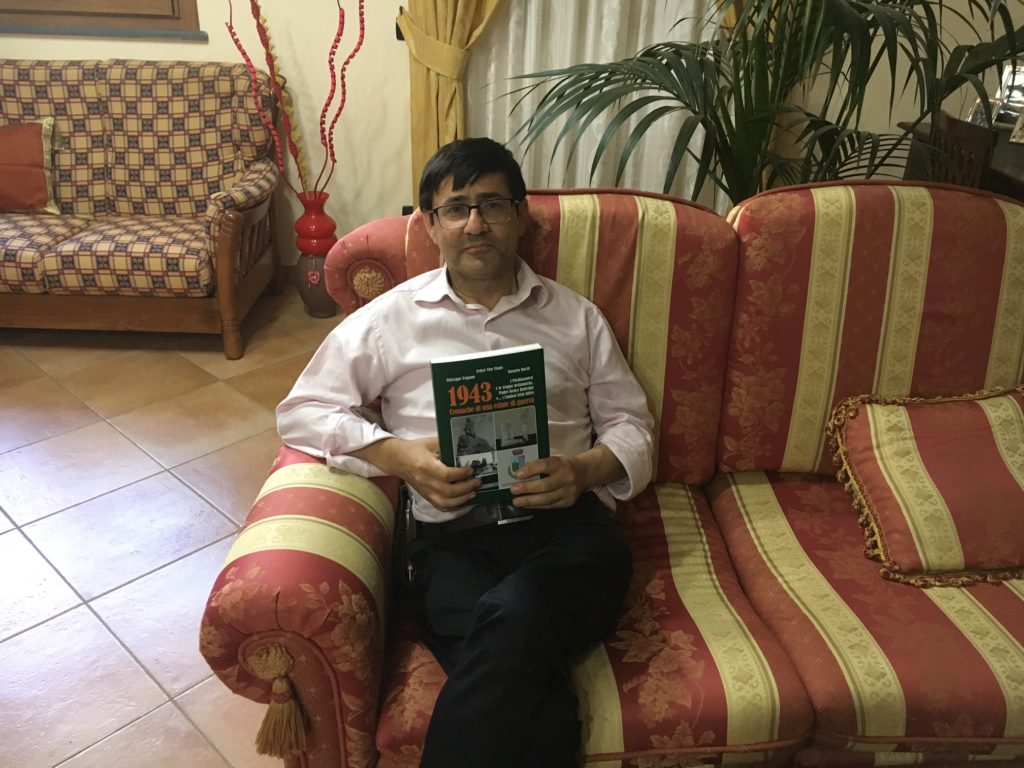

During the recent Association visit to Sicily, we were delighted to receive a copy of a new book outlining the story of Piedimonte Etneo during the Second World War written by our friend Dr Felice Vitale. The book, which has been privately published, relates the background to the events of August and September 1943 when British troops stayed in the town after the final liberation of the island.

For the London Irish Rifles, in particular, it was a most memorable stay as the men, who had been engaged in very heavy fighting during July and August, were able to relax as well as commemorate the 28th anniversary of the Battle of Loos with a parade and service for the 1st Battalion who stayed in the town for five weeks. In fact, the war diaries state that “Piedimonte was the most confortable place the Battalion had stayed in since they left England”.

Felice’s own mother, Angelina, and his grand parents had witnessed the entry of the London Irish Rifles’ pipers into the town and this allowed him to gain a unique insight into the feelings of townspeople as they were being invaded by a large group of friendly Londoners with a very distinct Irish flavour.

The book is currently only available in Italian and can be viewed in the Regimental Museum and we hope to add a translated version to the website at some future time.

Great work indeed.

Grazie Mille.

Rifleman Louis Jeffrey

We are pleased to receive a note and some photographs from Chris Jeffrey with information about his father Louis, who served with the 1st Battalion in the UK, Middle East and Italy during the Second World War. Rifleman Jeffrey first joined up with the London Irish Rifles in May 1938 and was finally demobbed in June 1946.

In his note to us, Chris said:

“I know my father was based with Lord Gault’s HQ at the outbreak of war as an interpreter. Obviously they were forced to withdraw but I’m not sure if they got out via Dunkirk or Cherbourg.

This picture was taken in Mersham sometime in 1940/41 and shows the Pipes with Tara the Irish Wolfhound and Mascot. I believe my father was based in Hatch Park which was part of the Brabourne Estate before deploying to the Middle East. Part of his duties at that time was patrolling Romney Marsh on his motorcycle. He also met and married my mother, Mona, who was living at the time with her parents lived at Hatch Lodge – her father, my grandfather, had worked on the Brabourne estate.

This picture shows my father with the CMF in 1945 enjoying some skiing in Cortina which can be seen behind the group. My father is sitting on the ground far right at the front.

I know my Father was wounded at Anzio and sent back to Blighty to recover. He eventually arrived back at the Depot in Ballymena but I’m not sure how long he was there before returning to Italy to rejoin his Battalion.

He spoke fondly of his CO, Colonel McNamara, who was sadly killed by German mortars in 1944 while visiting the Bn as they were moving into the Senio Line. “

Sergeant Pat Sweeney, 1st Battalion

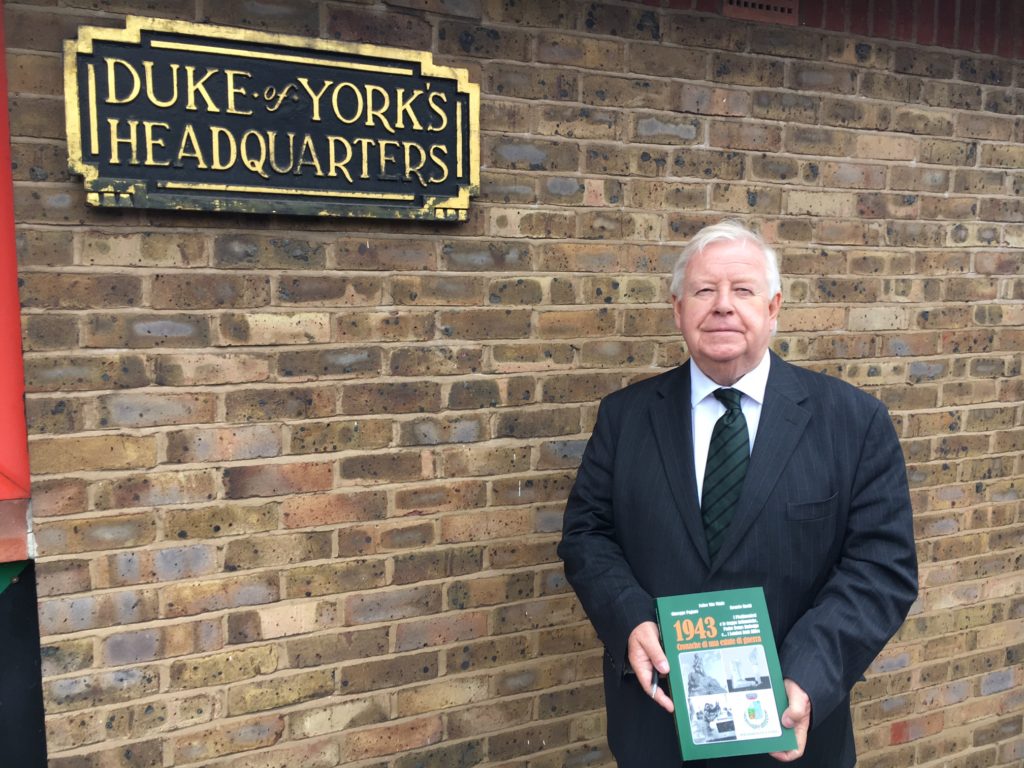

We’ve received some tremendously evocative photographs from David Sweeney, the son of Sergeant Pat Sweeney, who served with the 1st Battalion London Irish Rifles throughout the Second World War. David told us that his father, who was born in 1912 in Galway, joined the London Irish before the war when, at the time, Pat lived with his family in Chelsea very close to the Duke of York’s HQ.

Sergeant Sweeney served with the Carrier Platoon during all of the 1st Battalion’s service period overseas in Iraq, Sicily and on the mainland of Italy – a remarkable journey indeed as he remained largely unscathed during the various battle periods, including the attack on Fosso Botacetto, the ascent of Monte Camino, the crossing of the Garigliano river, the defence of the Anzio beachhead, the assaults on the Gothic Line and the final advance towards the Po river.

At the end of the war, Pat remained with the London Irish Rifles until the mid 1950s and was a very well respected and popular presence for many years at ‘Club Nights’ and parades at the Dukes. Pat married Ann in the late 1930s and the growing Sweeney family would later move to Greenford – though perhaps that location was less convenient for enjoying too many late nights at Sloane Square!

We would like to thank David Sweeney for sharing this gallery of fantastic photos.

Quis Separabit.

.

.