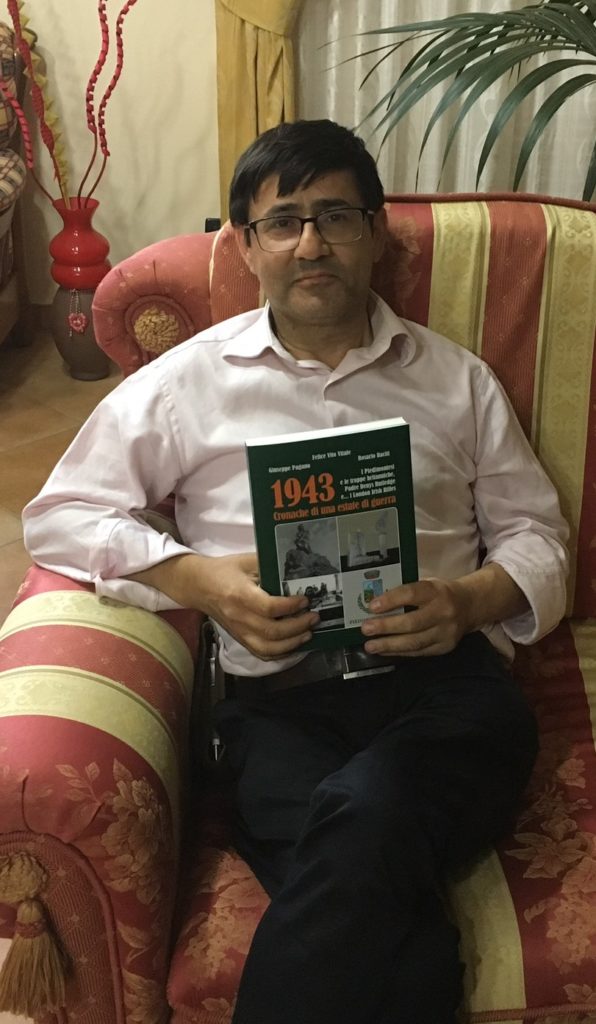

We were recently delighted to receive a copy of a meticulously researched book, co-written by our good friend Dr Felice Vitale, describing the experiences of Sicilian civilians during the desperately difficult period when war came to their island in 1943.

By kind permission of Dr Vitale, we are now able to reproduce below a translated excerpt of the moving account of the stay of the 1st Battalion of the London Irish Rifles in his home town of Piedimonte Etneo during September and October 1943.

Wednesday 8th September 1943 marks the beginning of the London Irish Rifles’ stay in Piedimonte.

On their arrival in the town, it was a festive atmosphere and the welcome was extremely warm from the local population.

Many of the men were wearing kilts, some playing the bagpipes. Mrs Venera Pagano remembers that there was a big party when the soldiers came in, “dressed a little strangely, not as good as the Italians” because they wore “skirts”. The London Irish people distributed sweets to the villagers and received constant applause.

Angela (Angelina) Belfiore, who was 21 at the time, heard sounds from the square. Her father ‘Mastro’ (it means very skilled in his job) Felice happily invited her to go out and off to see the “Scottish” as they crossed the main street. Angelina saw those soldiers with “skirts”, some of which were orange coloured (saffron). Only after some time did she and her father understand that the men were not actually Scottish but in fact ‘Irish’.

In September 2019, Angelina recalled the events of 1943.

When the London Irish crossed the Corso near the Mother Church, some citizens, looking out from the balconies in front, threw flowers onto the marching soldiers. The London Irish Rifles stayed at many of the buildings occupied previously by the ‘Hampshires’ and established the headquarters of their command in the villa of Baron Pennisi Floristella in the Zappello di Campagna district.

Despite the displacement that had occurred, some of their soldiers showed the symptoms/signs of malaria, which was linked to their stay in Fiumefreddo. In part, these soldiers were hospitalised in the upper floor of the Villa of Lio Micceri near the Convent. Ms. Angela Micceri, who at the time was an eight- year-old girl, remembers that the rooms on the upper floor of the villa received dozens of cots in which the feverish soldiers were dealt with. In the diary of Corporal Rawlins, he too was feverish shortly after arriving in Piedimonte and his subsequent transfer to Taormina is described. There, in a hotel converted into a hospital, he received treatment with quinine. From the terrace of this hotel, he observed the summit of Etna coloured red in the evening hours. During that period, Etna was erupting – or it might just have been the glow of sunset !

Not long after, the corporal was released from the place of treatment and returned to Piedimonte. Rawlins, even though he was recovering, ventured on a march up to the summit of Etna along with the soldiers of his own company, We learn from the same diary that, among the ranks of the 1st Battalion, there was also some soldiers, who were visiting temporarily from the 2nd Battalion of the London Irish Rifles. Many things in Piedimonte were appreciated by the Anglo-Irish soldiers. In particular, the plentifulness of water, the possibility of staying in houses equipped with electricity and the presence of a cinema. The relations maintained with the inhabitants was also good. Salvatore (Turi) Ragonesi remembers that the soldiers with the kilts held him as a child on their knees and gave him good marmalade “from the peppermint jar”. Sometimes it also happened that Salvatore was invited to play football with the soldiers on the square in front of the church of San Michele. For this purpose a balloon was used, and made up with old rolled up rags. Mrs Giuseppa (Pippa) Vecchio was attracted by a platoon of soldiers with a large green checkered kilt that were housed on the ground floor, on the west side of Palazzo Salluzzo. They used to go up Via Salerno to go to the square and when they reached the height of his balcony up there, they threw cans of meat, inviting her to close the shutters first and take cover behind them to avoid being hit. The inhabitants of the Zappello di Campagna district, including Rosaria (Sarina) Vecchio and Salvatore Panebianco, traded agricultural products daily with British soldiers. Tomatoes, grapes and wine were bartered with chocolate, biscuits, tins of meat and occasionally with some shillings. In that district, in the Palazzo Pennisi-Floristella and in the surrounding estate, the Command of the London Irish Rifles was established.

Among the dozens of soldiers, who also were staying in nearby farmhouses, many wore kilts, played bagpipes and carried out intense activities of physical training. Mrs. Vecchio (Rosaria) also recalls that the inhabitants of the district were often hired to take care of the cleaning of the building used as the command post. She emphasises the politeness with which she was treated by the English. Even in Via Greci, currently in homes owned by the Brischetto and Di Bella families, a company of the battalion was housed.

The London Irish Rifles returned to Piedimonte Etneo in September 2016.

One of the soldiers housed there ran into a comical accident. It happened that he bought prickly pears by Mr Alfio Cassaniti and thoughtlessly picked them up inside of his shirt and immediately dropped them on the ground as soon as the small thorns pricked his abdomen and he had to resort to the care of the health personnel of a small outpatient clinic in an entrance hall of Palazzo Morabito. In addition to agricultural products, the Piedimontese community offered numerous other services to Anglo-Irish soldiers. Washing of clothes, by families living in Via Borgo and in the Ponte district, tailoring work, cutting of hair and even catering in the few taverns or pubs (Osteria is a shop where wine is the mainly offered thing) in the town. To put it in the words of Mrs. Concetta Amante (now over 90) “the English gave work to many Piedimonte families”. The story of the young Corporal George Willis, stretcher bearer and bagpiper of the battalion is worthy of note. He entered into a friendly relationship with a girl named Angelina (born Angela Venera Tomarchio) and her family. He got into the habit of playing his bagpipes in Via Borgo, beyond the columns of Porta San Fratello, perhaps also to make a call for that beautiful girl.

It was rumored that the corporal, at the time just 23 years old, had fallen in love with Angelina, but their bond would have been essentially platonic. Angelina’s father had died and she lived with her mother and her brother. Below is the text of an email sent by George Willis, son of Corporal Willis, to Richard O’Sullivan and sent to Dr Felice Vitale on 15th March 2016.

“..Yes it was an Angelina who did his washing etc and he was always appreciative of how she and her family adopted him. She was barely a teenager at the time and that might help confirm the link that Felice has tracked down…”

Also in an e-mail of 15th July 2016 George Willis adds more details to the story:

“She reminded Dad of the seven sisters he had back in London and he returned Angelina’s family hospitality and help (with his washing) with gifts from his provisions etc. “

So the Corporal felt that he was almost adopted by the girl’s family. He reciprocated the help that was given, especially in washing clothes and giving hospitality to the family by providing them with supplies or military rations. Angelina, meanwhile, despite having great affection for George reminded him that he had left seven sisters in England, who were waiting for his return. Angelina knew that George would soon leave Piedimonte and probably didn’t want him to suffer the farewells too much. After leaving Piedimonte, Corporal Willis was taken prisoner during the fierce fighting that followed the landings in Anzio in early 1944 and at the end of the war he returned to England where he was awaited by his sweetheart, Rose.

Although relations with the population were good and marked by mutual sympathy, the Piedimontesi, who had become ‘traders’, perhaps exaggerated a bit with their ‘business sense.’ In the pages of the book ‘The London Irish at War’, written by veterans at the end of the conflict, it is underlined how in Piedimonte the prices of every kind of service rose out of all proportion. A sudden increase in the cost of a haircut or a laundry service was observed. Perhaps it had been noticed by the rise in the number of cans of meat or packets of biscuits, in the quantity of shillings or of lire that merchants and citizens demanded from soldiers in exchange for the services provided.

The office of the Battalion Commander had to intervene energetically to moderate prices. The military began to write “out of bounds” on the facades adjoining any locals, who were considered inadvisable by soldiers in various capacities. At this juncture, the mediation activity of Dedy Ghandour, a British military man stationed in Piedimonte was decisive. He began to verify that the businesses adhered to the rules imposed by the British Military Command. In particular, he “experimented” himself in taking advantage of the excellent quality of the shaving service offered by the barber shop (or shaving salon) Puglisi where, together with the owner Salvatore, a future Knight of the Republic, and also where the young Antonino (Nino) Panebianco worked. The Salon Puglisi was located in Via Vittorio Emanuele II, on the ground floor of the present Palazzo Calì. Relations between the military and locals soon became normal. Dedy, in the meantime, had spotted a young girl who lived in Via Umberto. It was Melina Barbagallo. The first meeting was a bit ‘hectic’. In fact, the British used to requisition pianos to be used for the troops’ entertainment. One day, the British soldiers entered Melina’s house with the intention of taking over her piano. The family tried to dissuade the soldiers from their intent by pointing out that the removal of the instrument would have made the girl extremely sad. The English, including Dedy himself, asked Melina to play to show that she knew how to use that instrument.

After that, Dedy repeatedly went to Melina’s house with the excuse of listening to her play. The girl replied positively to the young soldier. On their love, it was compelling and impetuous as can be, bearing in mind their youth. But even for Dedy, it was the time to leave Piedimonte. He promised Melina that he would return for her as soon as possible.

Many years passed following their farewell. It seemed that Dedy had already forgotten about Melina and also because an accident had temporarily and partially erased his memory, but one day, here was a man knocking at the girl’s door. The father looked out and asked who he was. Dedy replied “I am his daughter’s love”. Dedy was back. He brought a ring as a token with as much glitter as there had been years since their last embrace. Melina and Dedy would marry in the Mother Church of Piedimonte shortly thereafter.

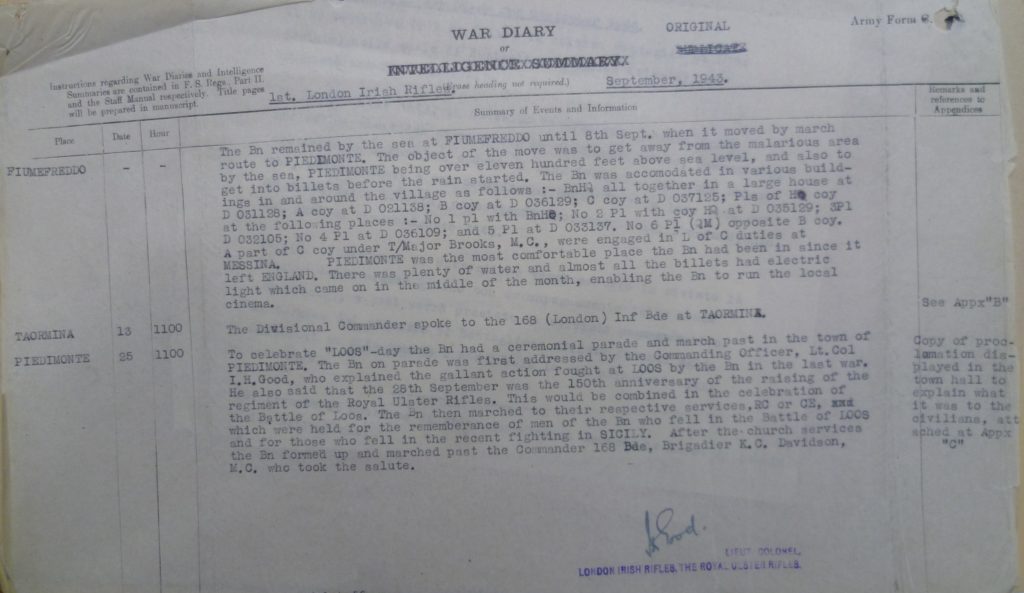

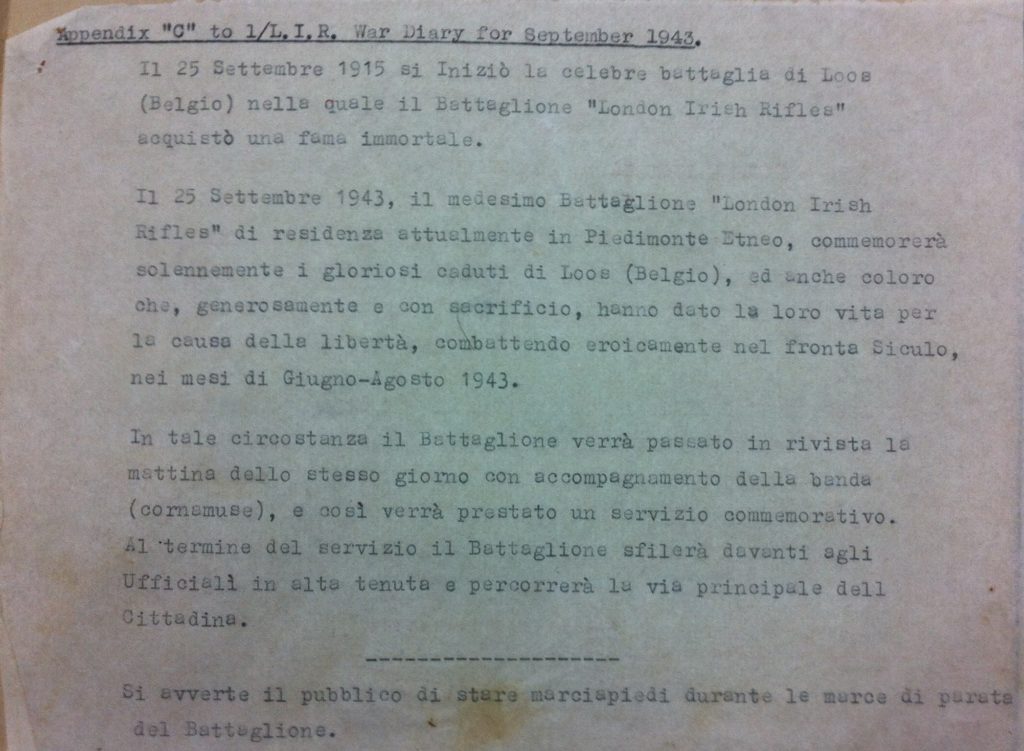

Right back to those weeks of September, the Battalion was then working at full capacity in the preparations for the celebration of the so-called ‘Sunday of Loos’ or ‘Loos Day’, which was scheduled for 25th September 1943.

To understand what the ‘Sunday of Loos’ meant for those soldiers, it is necessary to go back a few decades to 1915 during the early part of the The First World War. On the twenty-fifth of September of that year, on the western front, in the territory of Loos-en-Gohelle in France, the London Irish Rifles were lined up in front of the German trenches waiting to go on the attack. All of a sudden, Sergeant Frank Edwards (1893-1964), captain of the Battalion’s football team, pulled a leather ball from his backpack. In order to give courage to his fellow soldiers and push them forward to attack, he threw the ball towards the enemy trenches and kicked it vigorously, leaving the Germans, who were entrenched a few hundred metres away, astonished. That day, the London Irish surprised their opponents and fought with great bravery. On account of those deeds, the Battalion received great recognition. From then on, and up to the present day, the Regiment celebrate that anniversary on the Sunday closest to 25th September.

In Piedimonte, on Sundays it was also usual to see the kilt players of the battalion crossing the Corso Vittorio Emanuele II spreading music through the bagpipes. That Sunday appointment had become unmissable also for Mrs Antonietta Scidà. At that time, Antonietta was still a child but she well remembers the bagpipers of the London Irish wearing the typical baggy green ‘beret’ – the caubeen. In addition, the military chaplain invited not only the military but also civilians and children to participate in Mass on the parvis floor of the Mother Church. The British military, by the hundreds, as had been reported in an interview with Mr. Venerando Pappalardo, attended the mass standing up and banged their heels at the solemn moments. After the mass, sweets which Antonietta was very greedy to consume, were distributed to the children.

At that time, the Military Chaplain of the 1st Battalion, London Irish Rifles was Father John Antony Treacy, He was born on 18th February 1913 and had his first posting as a Military Chaplain in 1941 and served with the London Irish Rifles until 1946. During the preparations for the celebration of “Loos Sunday”, Piedimonte’s small tailors were also involved. Leonarda Belfiore worked on the uniforms of the London Irish Rifles utilising the tailoring skills of Mrs. Lucia ‘a Surda’, near the Palace of the Prince Gravina Cruyllas, where today the home of the Barbarino family live. There, the soldiers’ uniforms were put back into ‘working order’. After the war, the Palace would be a little too hastily demolished in the name of ‘modernisation’.

A Commemorative Plaque marking the Service on Loos Sunday in 1943 was unveiled in September 2018.

The shoulder straps of the officers, in ornate fabric mounted on cardboard, were also sewn. In addition to the soldiers’ routine military activities, there were the also time for leisure for the Anglo-Irishmen. The cinema on Via Vittorio Emanuele III was put back into operation. The soldiers mounted a stage on which they performed songs and theatrical performances. Another place of entertainment was housed in the premises of the Russo-Puglisi pharmacy and the drugstore and tobacco shop of the Casella family used previously by soldiers of the 1st Battalion Hampshire, along the Corso Vittorio Emanuele II. Here, hot tea was served at tables by two Piedimontesi – one was Salvatore Intelisano and the other Salvatore Cassaniti. The adult Cassaniti would become Mayor of Piedimonte and a university professor.

The bagpipe players would frequently perform between the tables and the soldiers would sing songs especially during the visits of officers. A regular customer was Viscount Major ‘Monty’ Stopford, who used to dress with a short kilt. Nino Panebianco would see him entering and leaving almost every day. From reading the obituary of the Viscount, we know that he liked to perform traditional Irish songs and loved the convivial atmosphere. Also, General Bernard Montgomery probably attended that hangout before the arrival of the London Irish. We know that in the early days of September, Montgomery met several officers and soldiers of the 1st Battalion Hampshire Regiment in Piedimonte. It is possible that, after the meetings, he (General Montgomery) might have been invited to some refreshments in those local headquarters of the pubs that “Hampshires” had called “The Swede Bashers’ Arms”! On the stage set up in the local cinema, an American Army Orchestra would have performed. Both from the private diary of our fellow citizen Ignazio Del Campo and from the diary of 168 Brigade, of which the London Irish were also a part, we learn that the American Band twice appeared in Piedimonte. On one occasion, the concert was held on the Piazza del Convento and, based on what was learned from Mrs Angelica Morabito, we know that this Band found accommodation in the Palazzo Morabito in Corso Vittorio Emanuele II. Members of the Band of London Irish had for the most part previously been lodged in the Palazzo Morabito too.

Also in September, on the 23rd to be exact, Gracie Fields sang and acted in Piedimonte entertaining the London Irish. We can probably presume that Fields performed at the cinema in Via Vittorio Emanuele III. Mrs Gracie Fields, a professional actress, was born in Rochdale on 9th January 1898. When she was an established artist, she married an Italian citizen in 1940 but later that year, war when broke out with Italy, and at the suggestion of Winston Churchill, they emigrated to the United States of America. However, she returned to England shortly after and began working for the Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA), which organised shows for British troops. Gracie Fields later lived on the island of Capri where she died on 27th September 1979.

In any case, the long awaited moment for the London Irish arrived a few days later. On the morning of 25th September 1943 began the celebrations of the Regimental party that was the ‘Day of Loos’. The London Irish had planned for the bagpipers to play on the main street of the area but something wasn’t right – in fact, not all their musical instruments were available as some of these had not yet reached Piedimonte. This created a deep disappointment for the Battalion Commander, Lt Colonel Ian Good, and also because they could not play a tune written for the occasion by a Piedimontese musician. Even if the name of the musician is not mentioned in the writings of the Battalion, we can say with almost absolute certainty that that composer responded to the name of maestro Salvatore Averna. Nevertheless, the available instrumentation was sufficient to guarantee a musical service and the procession of the bagpipe players along the main street.

In addition to the parade along the main street in front of Brigadier KC Davidson, commander of 168 Brigade, the soldiers attended a solemn mass, which was celebrated in the Mother Church. The celebrant that day is recorded as “Father John Antony Treacy, Irish Chaplain”. In the harvest register, the Archpriest Cannavò pointed out that the Mass was in memory of the sacrifice of the English soldiers who fell in combat. In Latin were transcribed the words “Pro Anglis Martiris in Bello”. We know that during his stay in Piedimonte, Father Treacy, was lodged in the country-home of Pennisi Floristella-family. There, he received meals prepared in the English kitchens set up within the Palace of Agatino Scidà. At the end of the war, he was included in the list of chaplains of the Reserve Force until 1967 and in the last period of his life, Father Treacy was parish priest of Saint Joseph’s Parish in York, dying in 2006 at the age of 93.

In addition to celebrating the anniversary of the Regiment’s exploits in France, the London Irish solemnly saluted the gunners of 465th Battery of the 90th Field Regiment, Royal Artillery who had supported them during their recent fighting. In January of the following year, the artillerymen of the 465th Battery, in the meantime having already returned to England, received an official recognition from the London Irish Rifles for the important support they received during the Sicilian campaign . The ceremony took place in the small town of Whittlesford, near Cambridge. A silver statue of the ‘Man of Loos’ was given to the gunners.

The London Irish left Piedimonte on 11th October 1943 under a light drizzle. The then young Leonardo Arcidiacono, a future doctor, told us of the tears of one of the young soldiers as they approached their departure. The soldier was housed on the ground floor of the Palazzo Puglisi, between the Stiro laundry and the Belfiore house. When Leonardo asked why he was crying, he said that the next day the battalion would be on the march towards Messina.

A Memorial to the men of the London Irish Rifles was unveiled in Piedimonte in September 2016.

Who knows, maybe besides leaving the island, he left his girlfriend too? Of course, a large number of those young soldiers wouldn’t come back to England alive. The bloody fights of Anzio, Montecassino and other clashes along the Italian peninsula awaited them. Probably, in their hearts, they wondered whether they would ever again see their homes, their parents, their brothers or their sisters. And if fate would give them the chance to have a bride and become fathers. In the faces of the children of Sicily they had perhaps tried to imagine their own children that they hoped to have one day and as such they looked after them and cuddled them. Starting out on their long journey north from the town of Piedimonte, the soldiers left with the local people the many desires that so many of them would not have a chance to realise.

Less than two years after the London Irish Rifles left Piedimonte, the war would end. Nazism, an absolute evil, will finally have been defeated along with its unwary and improvident allies.