January and February of 1945 were among the coldest winter months recorded in Europe in the entire 20th century. In Silesia, then part of the Third Reich but now in Poland, temperatures fell to 25 degrees centigrade below freezing.

These were the conditions that faced Prisoners of War (POWs) at the Stalag VIII camp near Lamsdorf (now Gmina Lambinovice) when they were ordered to march west before the huge Soviet offensive that commenced in early 1945. Most of the POWs had been weakened by years of bad food. None had suitable clothes and they were now ordered to walk up to 25 miles a day. The evacuation was part of a massive movement from camps including the Auschwitz extermination camp in the path of the Red Army steamroller. It was a formula for suffering and death.

Around 80,000 men from Stalag VIII and other POW camps were driven west. They included David Moore, a native of Airdrie in Lanarkshire, who had been enlisted into The Cameronians in January 1940 before being transferred to the London Irish Rifles at the end of 1942, not long after he got married.

Moore had been dispatched to join the 2nd Battalion London Irish Rifles in North Africa at the end of November 1942 and was involved in the battalion’s battles in Tunisia, Sicily and along the Adriatic coast. In March 1943, he had been promoted to Lance-Corporal.

L/Cpl Moore was a section leader with No 7 Platoon, E Company when they were posted in January 1944 to a patrol outpost north-west of the village of Montenero in the upper reaches of the Sangro river valley. The battalion’s role was to watch for patrols from a German Mountain Regiment, which were harassing the Allied front line in the Abruzzi mountains 40 miles east of Cassino .

Lacking winter equipment and camouflage, E Company had been camping out for several days in deep snow drifts on Il Calvario, a high point more than 3,000-feet above sea-level. On the morning of 19 January after another freezing night, Moore was attending an ‘O’ Group with other section leaders in the tent of 7 Platoon commander, Lieutenant Nicholas Mosley, when German ski borne troops attacked. A mortar shell hit a tree about a foot from the door of the tent, injuring a couple men including Moore who suffered wound to his arms and head. Mosley ordered the riflemen into their trenches and to prepare to put up resistance, but they were quickly surrounded, Five London Irishmen had been killed in the short battle.

Most of 7 Platoon were taken prisoner including Lt Mosley himself, though he and three others managed to escape their captors as a result of a partially successful rescue by E Company’s reserve platoon and led by Company Commander, Major Mervyn Davies. David Moore and 19 of his comrades, some without boots, were marched under armed guard through deep snow into the mountains north of the Allied lines and he was then treated for his wounds at a hospital in Florence. At one point, when he awoke and saw the distinctive uniform of the nurses, Moore had thought that he had “died and gone to heaven”.

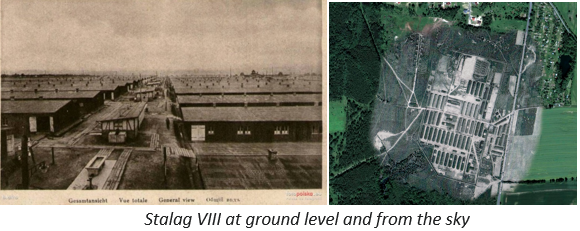

From Italy he was shipped by train to an enormous complex of POW camps in Silesia. His destination was Stalag VIII-B in Lamsdorf, which was also known as Stalag-344. The camp was originally built for no more than 15,000 but, by the end of 1944, it held an estimated 49,000 men, including more than 3,000 Allied prisoners. The military hospital and the infirmary of the camp were always overcrowded. Inspectors from the Red Cross criticised the poor conditions of the clothes of most prisoners and the lack of medication in the military hospital. In winter, the barracks were barely heated and, by 1944, there was a lack of water. Russian and Italian prisoners would be denied all medical assistance.

“(It was a) time he didn’t say very much about,” his son David Moore says. “On his release he said that his treatment had been reasonable though food was in short supply. Red Cross parcels helped to keep him alive.”

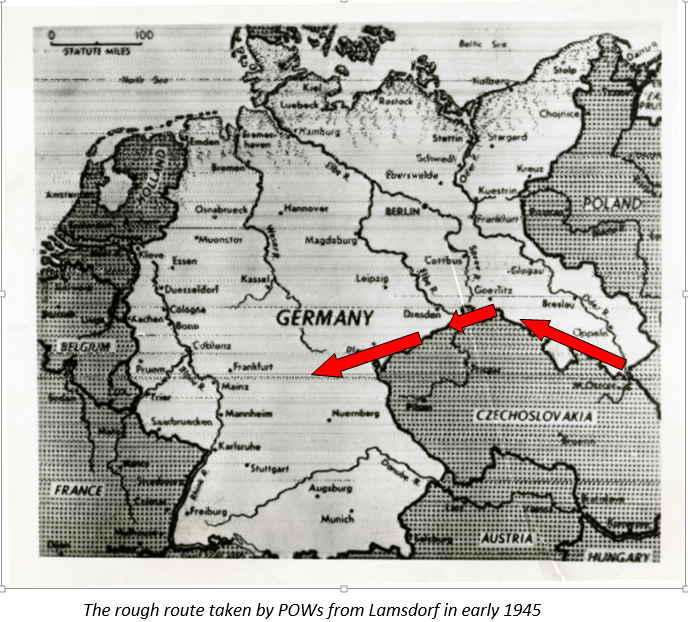

This was to change for the worse when the camp was evacuated in February 1945 when POWs were marched out in groups of around 200 into an arctic landscape. The Germans provided farm wagons for those unable to walk and teams of POWs often pulled the wagons through the snow because of the lack of horses. The reception was mixed in the German villages that they passed through on their journey west. There was occasional hostility and rocks were thrown by people angry about Allied bombing while on other occasions, penniless people shared whatever little food they had. At night, those with intact boots who risked taking their boots off to avoid trench foot found they couldn’t get their swollen feet back into them in the morning. Boots froze and were sometimes stolen. There was almost no food and the men had to scavenge, eating rats and cats to fend off starvation. Dysentery and frostbite were common and there were cases of typhus, which was spread by body lice. Some men died of exposure while they slept.

As the weather slowly improved in March, the widespread thaw turned roads into a quagmire of mud. Many POWs marched more than 300 miles before they reached Allied armies advancing into south-west Germany. Up to 3,500 British, Commonwealth and American POWs are estimated to have died in what is known as “The Death March.”

“It was a nightmare experience for my father,” his son says. “He spent the next ten weeks walking between 15 and 30 kilometres most days until he was finally released by Allied soldiers and repatriated to the UK. He suffered all the privations recounted by many who took part in and survived this horrendous experience including bitter cold and extreme hunger. I recall him speaking about it only when he recounted the kindness that he and a pal were shown by a German woman who cooked them a good meal when they arrived at her door with only a handful of rice and had asked her to boil it up for them. By the time he got home, he was suffering from flat feet, damaged ankles and metatarsalgia as a result of prolonged standing.”

After recovering his health, David Moore was transferred to the RASC where he remained until he was released to Army Reserve in May 1946. He then returned home to his wife Sadie in Scotland and they would have two children, three grandchildren and two great grandchildren who knew him, plus two others who were born after David’s death, at the age of 92, in January 2009.

A most remarkable story of human resilience.

A memorial was later erected on the site of Stalag VIII in memory of the thousands who died there and during “The Death March”.

The inscription on the sandstone plate next to the memorial reads: Stalag VIII: A place sanctified by the blood and martyrdom of the prisoners of war of the anti-Hitler coalition during the Second World War.