Captain Ernest May enlisted with the London Irish Rifles at the outbreak of the Great War at the age of 17 and he would go onto serve with the 2/18th Battalion (2nd Battalion, London Irish Rifles) in France, Salonika, Egypt and Palestine.

After he was demobilised in 1919, Ernest went into business in London and would become a Vice President of the Regimental Association. During the Second World War, although past the age of call up, Ernest again responded to the call of duty by taking charge of the Cadet Company as well as undertaking a considerable volume of welfare work amongst ex members as well as the dependents of the men serving overseas.

After the war, Ernest continued his interests with the London Irish Rifles and would arrange annual reunions of men from the 2nd Battalion and would eventually be able to complete the story of the 2nd Battalion,”Signal Corporal” in 1972.

Captain Ernest May died on 7th December 1980 at the age of 83.

“On 31 August 1914, authority was received for the 2nd Battalion to be raised and it was complete on 5th September. The number enlisted was 1,050 and a few officers and colour sergeants were lent to us by the 1st Battalion.

At that time, a battalion consisted of eight companies and that was our formation for some months.

The Commanding Officer was Lieut Col Matthews; the Second in Command, Major Scott Allan and the Adjutant, Captain Curtis. The eight company commanders were Captain Sladen, Payton, Archer, Harding, Freyer. Thrussel, Newton May and Beamish. Among the junior officers, I recall the brothers HA and HS Lane, Skevington, Jacob, McClure, de Ferrars, Wanklyn, Barnett, Barber, Ashby, Champion, and the three Ds – Deacon, Dale and Dircks. The Medical Officer was Captain Burrows.

As Territorials, we could not be sent overseas, so after about a week, we were invited to accept what was known as the foreign service obligation and, some six months later, when those who had not accepted this obligation were withdrawn and sent to a home service unit, we found that only fifty only were involved. We took a poor view of these people at the time but – who knows what is in another man’s mind? A few months before we left for France one of them returned to us – a man who had been pretty close to me in the early days and told me why he had not felt able to risk his life or disablement at the beginning. His responsibilities had now lessened, so he rejoined us – and happened to be one of the first killed in the line in France. There will still be some who remember Rifleman Gates.

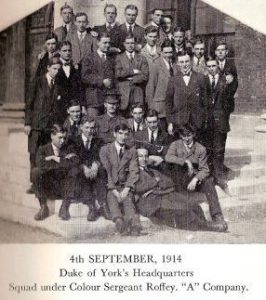

For the first few weeks, we lived at home and reported to the Duke of York’s Headquarters each day but as the parade ground could not hold more than 500 for squad drill, half the battalion worked from 9am to 1pm and the other half from two o’clock onwards. I recall that for the first week, I was on the morning shift and so was able to enjoy my afternoons and evenings on the river above Hampton Court. The afternoon shifts for the second week put an end to that, and for the first time it was brought home to me that the war might well interfere quite seriously with my private avocations. It did.

For the full battalion to train together, we used Hyde Park Park and Sergeant Keen recalls a meeting with Winston Churchill – then First Lord of the Admiralty. “A” Company were marching into Hyde Park, in civvies of course, when a horseman wearing a square bowler signaled the Company Commander to stop. Captain Archer recognised Winston at once. He asked who they were and, on being told, congratulated Captain Archer on having such a fine body of men, adding, “I’ve not see a finer set of men. Not even in the Guards”. The Company marched on into the Park, all feeling inches taller. As Sergeant Keen remarks, “What a tonic for morale”.

On 27th October, we moved to quarters in the White City, being accommodated in the large Exhibition Buildings and, within a few weeks, suffered a severe blow in the loss of 300 of our number, who were transported to our 1st Battalion at St Albans. This was the first and largest draft, but others followed before the 1st Battalion left for France in March 1915. In all, we had sent about 500 of our best to our 1st Battalion by that date.

In the rush to recruit at the start, many had been accepted who were well below the minimum age of 19 years – on their declaring they were 19. These “frauds” had been discovered and their true ages recorded within a short time. Another substantial number were commissioned and left to serve with other regiments. By the middle of 1915, we were but a shadow of the original battalion – and small drafts continued to leave up to the end of 1915. The White City photograph taken in November 1914 is perhaps representative of what happened with the original battalion, so I gave the subsequent history of each in my footnote.

The only point on which this photograph may not be truly representative of the whole of the original battalion is that the proportion of those under the minimum age of 19 years was possibly somewhat higher than one in six. Note that we are in uniform only from the waist down. However, each is wearing a buttonhole consisting of a London Irish Rifles’ button backed by a piece of green fabric.

Our training areas and dates of moves were:

1915.

Jan 2nd – From White City to Reigate.

Mar 29th – From Reigate on St Albans, where we followed a few days after the 1st Battalion left for France and found large numbers of young women very disconsolate. We felt it to be our duty to console them and they were soon quite happy.

May 11th – From St Albans via Hertford and Bishops Stortford to Braintree.

June 24th – Braintree to Hatfield Broad Oak.

Oct 25th – Hatfield Broad Oak to Saffron Walden.

1916.

Jan 23rd – Saffron Walden by train to Sutton Veny (Warminster).

June 23rd – Sutton Veny to France, arriving 24th.

It was only after arrival at Sutton Veny that we were properly equipped, exchanging our Japanese rifles for the Short Lee Enfield and having plenty of firing practice with these.

In December 1915, authority had decided that 60th Division should no longer find drafts for their 1st Battalions in the 47th Division but should be prepared for overseas service as a Division and a new Divisional Commander was appointed – Major General ES Bulfin CB, a soldier of distinction, who had commanded a brigade in France since the first days of the war.

At Sutton Veny, we said goodbye to the somewhat elderly brigadiers and battalion commanders, who had worked so hard to train us, their places being taken by younger “Regulars” with battle experience in France.

Our new Commanding Officer, Lieut Colonel WH Murphy had had no experience since 1902 when, as a Lieutenant in the 1st Leinster Regiment, he left the Army at the end of the South African war, in which he served from 1899 to 1902 and was awarded the Queen’s and King’s War medals with eight clasps. After a Senior Officers’ Course, he came to us and soon had the confidence, in fact the admiration of the whole Battalion.

During the first months of 1916, the battalion was built up to full strength with absolutely first class material and, by the time we left for France, no one could have wished to go on the great adventure in better company. And the 17 year olds of 1914 were now 19.

Before leaving this training period in England, let me recall two inspections.

The first was in January 1916 while we were at Reigate, when we were inspected by Lord Kitchener, the Minister of War, on Epsom Downs. At 515am, we moved off from Reigate with “haversack rations” (no haversacks) and about 545am, snow began to fall. At 745am, we reached Epsom Downs, the snow being then about 4” deep. After waiting about until 0945 while snow continued heavily, we then moved to our inspection position where we were “dressed” by the left, by the right, by the front and by the rear until about eleven o’clock. The Battalion possessed about fifty rifles, which were passed to the men in the front rank!

We were drawn up facing the road, which runs across the Downs and there were dense masses of men to the right and the left as far as the eye could see when, soon after eleven o’clock, Kitchener drove past at about thirty miles an hour with three French Officers in his car.

We then marched to Reigate with snow still falling and, by this time, at least 8” deep. While marching down Reigate Hill, I still recall with joy the sigh of that mighty man, Regimental Sergeant Major Higgins (who was behind the big drum, which was being carried horizontally), slipping, shooting under the big drum on the seat of his pants and scattering half a dozen bandsmen in front.

I learnt many years later that the object of the exercise was to convince the French that we really had got a few millions of volunteers strenuously fitting themselves to carry on the war and the French were taken so quickly all over the country that it was impossible for Kitchener to switch men about and so have them inspected them.

The second and last inspection was one of the most beautiful sights I have ever seen.

Perhaps the mists of time have added enchantment to the memory but – on or near Longleat, the home of the Marquess of Bath, is a straight stretch of road a mile in length with rhododendrons some twenty feet high on each side. A few weeks before we left for France, with everything in perfect bloom, the Division marched along this road for inspection by King George V who, accompanied by a large party, was half way along. The time was late in May – a really glorious day such as is to be found perhaps only in this country in Spring or early Summer.

It was for us a great occasion – and the setting was perfect…

And so to war.”

Read the War Diaries of 2/18th Bn for the period: