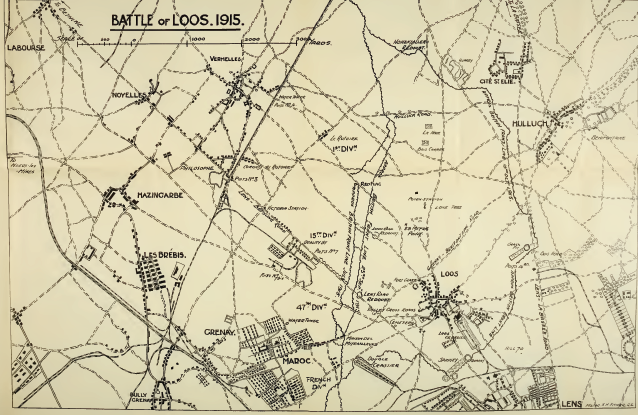

The Attack Begins.

At 4am on 25th September, there was a slight westerly wind, with a suggestion of south in it, and Division confirmed the order for smoke and gas to be released at 550am. Punctually, in a drizzle of rain, gas and smoke were released from the cylinders and began slowly to roll towards the enemy lines. The artillery, which had been firing at a slow rate during the night and early morning, opened a heavy bombardment on the enemy front line and supports. Realising the danger, the German artillery promptly retaliated and soon high explosive shells were crashing into the British trenches, while shrapnel screamed and burst overhead. The enemy infantry opened a heavy fire with machine guns and rifles. The shelling was severe and the din ear splitting, but owing to the depth and good construction of the trenches, casualties were few at this stage.

Gas and smoke were released alternately and soon the whole front was obscured. Dense clouds of white, yellow, brick red and black smoke, sixty to eighty feet high rolled slowly forward – billowing and eddying in the gentle breeze. The cloud was pierced by the blinding flashes of a multitude of shrapnel bursts and swirled and quivered under the shock of shell explosions. Meanwhile, the troops in the trenches stood to arms, officers gave final instructions and men looked to their rifles, bayonets and gas masks. Bombers tied to their sleeves the brassards to be used for igniting the ball bombs. Scaling ladders were fixed against the trench sides ready for the assault.

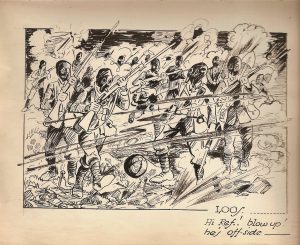

The London Irish Footballers.

In “A” Company’s lines, Rifleman Frank Edwards, who had conceived the idea of dribbling a football into the enemy trenches was busy using his breath to blow up the ball, which had previously been deflated by his Lieutenant’s orders. Elsewhere, a few riflemen, amused at their Platoon Sergeant’s hopes of a “blighty” one, schemed to trick the Sergeant into believing himself hit. One of them scraped a lump of clay from the trench side, rolled it into a convenient size and hurled it at the unsuspecting sergeant. Feeling a staggering blow on the side of his face, Sgt L… gleefully shouted that he had been hit. The realisation that the liquid running down his neck was not blood but muddy water and the laughter of his men quickly brought the Sergeant back to a sense of his responsibilities.

Along the whole front, the artillery battle raged but, after a time, the German shelling became noticeably wild and patchy and, by 615am, the infantry fire had slackened appreciably. At 620am, the wind changed slightly and the gas and smoke began to drift back. The alarm was given and gas helmets were at once adjusted. A few men, who were not quick enough in adjusting their masks, fell to the floor of the trench, writhing and choking in an agony of suffocation as the chlorine worked on their lungs.

Over the Top.

At 630am exactly, the signal to assault was given. Simultaneously, and led by the officers, the men of the London Irish climbed rapidly out of their trenches, formed up at five paces intervals and moved forward in quick time as on parade.

Rifleman Edwards threw out his football and, with his friends, Rifleman Micky Mileham. Bill Taylor and Jimmy Dalby, passed the ball from one to the other until it was lost to sight in the smoke cloud, as a flying kick sent it hurling towards the German front line. The heads of the attackers were shrouded by large blue grey flannel gas masks and through the large, round, goggles, intent eyes stared, while the projecting outlet of the mouthpiece rose and fell as the men moved and breathed. The cowled figures, with rifles and bayonets “at the “ready” hung about with picks, shovels, bags and bombs and other impediments – exaggerated to giant size by the effect of the smoke and gas – presented a fearsome spectacle and might well strike terror into the stoutest heart as they pressed forward.

In precise time and order, the second and third waves rapidly followed the first and were soon lost in the smoke and fog. The fourth wave moved from the saps into the assembly trench, spaced out on the Battalion frontage and followed the third wave approximately 150 yards in the rear. By this time, the leading waves were approaching the enemy front line, Lt Dircks found his puttees coming off and halted to re-fix them, while his self-constituted bodyguard, Rifleman S Farmer, cheerfully advanced with a superb “Charlie Chaplin” gait about ten yards in front of Lt Dircks and struck a theatrically fierce attitude of defiance. Fifty yards away, Lt Dale, the smallest officer in the Battalion, tried in vain to lead his men but was frustrated by his devoted troops, who insisted on getting in front to screen him from flying bullets.

The smoke cloud was thinner as the leading waves passed over the battered German wire and the enemy front line, now in full view, was seen to be thinly manned but the garrison threw out bombs and blazed away with their rifles at the advancing troops. Bullets and bombs found targets and men drooped dead and wounded as the leading waves, snap shooting and hurling grenades jumped the well battered German front line and pressed on towards the second line.

On the left, the kilted Highlanders could be seen moving forward in splendid style; on the right, men of the 6th Battalion advanced and beyond them the gallant “shiny Seventh” could be discerned, clambering up the precipitous sides of the Double Crassier, while the garrison fought the attack with bomb and rifle. As the London Irish leading waves surged on to the second objective, now quite clear of smoke, a battle royal was being waged in the front line.

The enemy, reinforced by men who had emerged from dug outs and with machine guns firing, faced both sides, shooting in the back of the troops, who had passed and resisting the Battalion’s last wave. Major Beresford, in charge of the line, was shot through the chest but saved many lives by directing the advance clear of a machine gun, which had accounted for him and a number of other men. A red haired German shot Lt Ashby through the leg and very many other casualties occurred until the London Irish fifth wave, composed of Battalion HQ, “B” Company and grenadiers, reached the trench.

Two platoons and the grenadiers, leaping into the enemy front line, fought the desperate Germans with savage fury. A party of London Irish grenadiers, assailed on both flanks by the enemy, bombed and fought with courageous skill as the enemy closed and succeeded in forcing the Germans to surrender, after having exacted a heavy toll in dead and wounded. All resistance overcome, contact with the German front line was quickly established, with the 6th Battalion on the right and the 15th Division on the left. By this time, the Battalion, depleted by casualties, but still in splendid order and now breathing freely with gas masks rolled back, pushed down the slope with parties of the enemy fleeing behind theme. Sgt Kemp and his platoon, suddenly confronted by a group of Germans occupying a position in a communication trench, attacked with vigour and, after killing fourteen, put the remainder to flight.

At Valley Cross Roads, the enemy, holding the ruined buildings and resisting stubbornly, checked the advance with fire from broken roofs, windows and gaping holes in the walls. Bombers were called for “at the double” and, without delay, men of the grenadier platoon rushed forward. Here was a task fit for the champion Bombers of the Division and, standing in line, twenty paces from the ruins, the Bombers hurled their grenades, with deadly effect, through the roofing, windows and broken walls. The enemy opposition was quickly smashed and, leaving 41 dead Germans in and around the ruins, the advance swept forward up the gentle slopes leading to the second line. Quickly, the Battalion clambered over the wire protecting the enemy’s second line and took possession of the unoccupied trench, while Bombers secured the flanks and cleared the house and communication trenches in front.

On the Battalion’s left boundary, a number of Germans sniped from the Cemetery but were speedily dispersed after a hide and seek battle among the tomb stones. As consolidation was commenced, 2nd Lt Pratt of No 15 platoon saw a body of the enemy advancing across his front. Work was at once stopped and, getting his men lined up in the prone position outside the trench, 2nd Lt Pratt engaged the enemy with rifle fire – he, himself, kneeling immediately in the rear giving range and target exactly as though on manoeuvres. The Germans were soon scattered but the gallant young officer was too exposed to be missed and was killed.

The Objectives Attained.

By 7am, the whole of the Battalion’s objectives were taken and the German second line occupied from a point 50 yards north of the Cemetery on the left to the junction, with the 6th Battalion on the right at the Bethune-Lens road. According to the plan, the 20th Battalion on the right and the 19th on the left, came up and swept through the London Irish front and advanced on their objectives. With the 15th Division working through the village on the north and the 19th and 20th Battalions in the south, Loos was soon in British hands.

A German light high velocity gun firing from the Copse on the high ground on the right, shelled the barricade, which was being thrown across the road to Loos below the Cemetery. Rifleman Ripley of the Grenadier platoon was killed by the second shot. At this point, a captured German officer stood by, smoking a cigar, watching with amused interest the efforts of the troops to dig a trench with entrenching tools across the pave road. As each blow with the entrenching tools merely produced a shower of sparks and made no impression on the granite blocks which surfaced the road, there was some excuse for his mirth.

Two or three women and some children, who had been living in Loos, were passed through the Battalion lines during the morning and escorted back to safety. The London Irish attack had achieved remarkable successes. Within 30 minutes of the time fixed for the assault, the Battalion had carried its first and second objectives, penetrating into the enemy territory for approximately 1,500 yards, clearing the way for the following troops. Direction had been maintained astonishingly well and, on arriving at the second German Line, only two platoons (from “A” Company) were off their allotted frontage, in spite of the fact that the enemy’s positions at the outset were enveloped in a dense cloud of smoke.

The battlefield presented a most animated picture. By contrast with normal conditions, when no human being for miles showed so much as a finger, hundreds of men moved freely in the open. Many were busy consolidating captured trenches, while processions of walking wounded and stretcher parties struggled painfully to the dressing stations. Prisoners were being escorted to the rear, runners hurried to and fro while long strings of men, laden with boxes of bombs and small arms ammunition made their way up to the firing line.

By 930am, the whole of the objectives of the Brigade were captured, except the south west corner of the Copse (part of 20th Battalion’s objective). On the right, the 140th Brigade had secured their objectives and, on the left, the 15th Division pursued the enemy beyond Hill 70 (just to the east of Loos). Further north, practically no progress was made and the left flank of the 15th Division was “in the air”. This circumstance, combined with the fact that objectives had been overrun, caused the 15th Division’s left to withdraw during the morning.

The German Counter Attack.

The enemy counter attacked the 7th Battalion at 930am on the west end of the Double Crassier, but was beaten back. At the same time, the 20th Battalion, in the Chalk Pit, were attacked but succeeded in repulsing the enemy. At 130pm, the Germans pushed forward over Hill 70 against the eastern side of Loos and one Company of the 17th Battalion was sent up to the support of the 19th Battalion, who had extended to the left to fill in a gap caused by the withdrawal of the extreme right of the 15th Division. Later, the situation east of Loos was reported easier.

During the late morning and afternoon, the volume of the enemy’s artillery fire increased considerably and the new positions and the old German front line were liberally shelled. Practically all movement in the open ceased, except on the roads where some transport and cyclists were severely punished.

At 530pm, men of the new 21st Division arrived. These troops had never been in action before, were foot sore and weary from their long march to the line and they had no maps nor accurate information as to the enemy front or even of the new British positions. They had the general idea of making contact with the enemy and getting what information they could from the troops in the support line. The men plodded on to the new forward area. Machine gun firing from the Copse raked their ranks and soon this advance wavered and finally petered out – some of the troops drifting away to the left into Loos and others returning to the support line in confusion, followed by the enemy’s machine gun fire, which inflicted heavy casualties while the men were in the open.

The London Irish Survivors hold the Objectives at Dusk.

Dusk found the Battalion occupying its objective in the second German line, and with consolidation well in hand. Every man had a serviceable fire step and the shallow portions of the old German line, which could not be deepened during the morning, owing to the lack of picks and shovels, had been excavated to a satisfactory depth.

The line was manned by the survivors of the day amounting to 12 officers and 300 men. Casualties incurred by the Battalion in the advance and during the day were 4 officers killed, 5 officers wounded, 66 other ranks killed and 144 wounded and 27 other ranks missing. Practically all the casualties had occurred at the enemy front line, very few men being hit after the front line was crossed.

A large number of Germans were killed and wounded and 20 to 30 prisoners taken. The moral and screening effect of the smoke and gas aided the Battalion’s progress, but on the London Irish front, none of the enemy was found to be suffering from the effects of gas.

Transport Problems.

When night fell, there was a good deal of work to be done. Parties of men were detailed to root up the wire defences of the enemy and to transfer the material to the forward side of the second German line. Large parties were organised to assist in the work of evacuating the wounded and other parties were sent down for rations and water. The night was cold and wet and the activity of the enemy’s light artillery helped to make the unpleasant conditions worse. On the left, there were frequent alarms and units of the 21st and 24th Divisions were withdrawing for reorganisation and other units of the same divisions were relieving units of the 15th Division.

The London Irish Transport section had an unenviable journey up with the rations. Conditions on the Noeux-les-Mines-Mazingarbe road were chaotic and progress intolerably slow but, after a gruesome journey across the scene of the Division’s advance, Lt McM Mahon and the London Irish Transport succeeded on reaching Valley Cross Roads where the Battalion’s carrying parties were waiting.

Lt McM Mahon proceeded to Battalion Headquarters and, after reporting to the CO (Lt Col Tredennick), was shown round the new line by Lt Blake Concanon and Capt HU Mann. When the Transport Officer returned to the Valley Cross Roads, congestion had increased to an amazing extent. There was a colossal jam of traffic on the Lens-Bethune road composed, apart from the infantry, of every sort of transport, gun limbers, ambulance wagons, water carts, GS and limbered wagons, practically all belonging to the Divisions, which had been sent up to exploit the initial success.

As was the case with the infantry, the transport of these units lacked forward area experience and needed guidance badly. In this connection, the work of Lt McM Mahon has never been properly appreciated.

With his experience and local knowledge of the Loos area, he was able, during the night, to be of considerable assistance. Lt McM Mahon made a special point of seeking out officers, giving them advice and detailed information. In particular, he emphasised the urgency of the transport being clear, before dawn, of certain areas, which were under direct enemy observation. Not all the transport was able to profit by Lt McM Mahon’s recommendations and, on the following morning, the German artillery took grisly toll of the exposed men, horses and wagons.

At daybreak on the 26th September, reinforcements of British and German troops were in position ready for action. On the front of the 47th Division, the night had passed fairly quietly and a firm grip was maintained on the captured area. The situation was not so good on the left flank of the Division. New troops, who had relieved units of the 15th Division, were reported by the 19th Battalion to be “nervy” and, as the morning progressed, this tendency did not abate. The 19th Battalion, in consequence, took special precautions in anticipation of possible events.