On 18 February 1944, further efforts were made to trace the Oxford and Bucks with no result, except to bring more casualties to the battalion. That night, Lieut-Colonel Good, exhausted by many days and nights with no sleep and little rest, was ordered by Brigadier Davidson to have a respite.

The position at that time was that in accordance with a plan prepared by the Brigadier, the London Irish, despite heavy shell and mortar fire, had got up forward as far as it possibly could. A strong, powerful blow would be needed to dislodge the Germans from their positions on the higher ground ahead.

Owing to the shelling, battalion headquarters had lost touch with the companies. Tactical Headquarters, commanded by Captain TJ Sweeney, the Adjutant, and accompanied by Captain A Mace and about ten personnel of the carrier platoon acting as headquarters defence, struggled all that night to reach the companies. They finally joined them at first light and found them sheltering in a wadi. Everyone was extremely weary and all further attack was out of the question for the moment. A Company now numbered about thirty-five men and C Company about the same. About an hour later the battalion suffered another severe blow. A stray shell landed near the resting men and Captain JR Strick, a very popular and efficient officer who had been with the London Irish from pre-war Territorial days, and CSM Flavelle, were killed and Major Brooks severely wounded.

To this depressing scene arrived Major Stopford, who as Second-in-Command had assumed control of the battalion in the enforced absence of Lieut-Colonel Good.

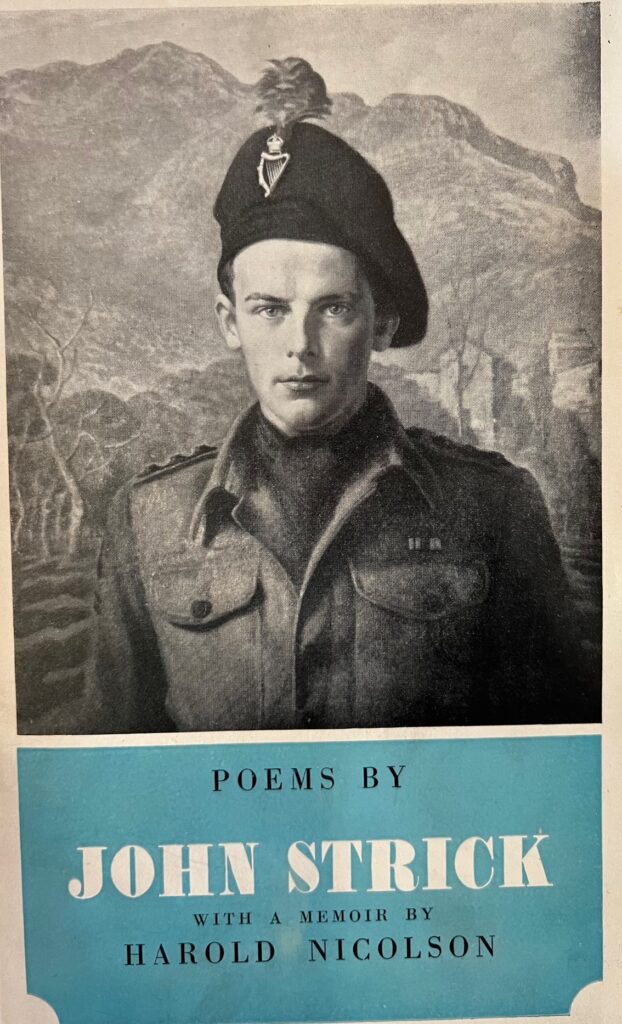

John Strick was killed in action on 18 February 1944 when 25 years of age. He was eldest son of Major John Arkwright Strick C.B., D.S.O. and Mrs Iris Gwendolen Strick nee Cammell. He spent the first eight years of his life in Edinburgh and at Worsley, near Manchester. In 1926, his father retired from the army and the family moved to Abbotsham Court, near Bideford. He was educated at St Aubyn’s Rottingdean (1927-1931) and at Wellington College (1932-36).

On leaving Welington, he went to Freiburg to learn German and thereafter spent a year at the London School of Economics. He subsequently read history at King’s College, London University where he remained until 1939. During his vacations, he travelled extensively in France, Switzerland and Germany and acquired a knowledge of languages which provide to be of great value to him during the war.

In April 1939, he joined the London Irish Rifles as a rifleman, before being granted a commission in September of that year. From May 1940 until November 1941, his regiment was stationed in Kent as part of the first line of defence against invasion. In November 1941, they transferred to East Anglia and in August 1922, they sailed, via Africa and Italy to the Near East. The early months of 1943 were spent in Iraq, in Syria, in Palestine, and in Egypt, training for the forthcoming invasion of Europe.

In July 1943, the 1st Bn. London Irish Rifles landed in Sicily as part of the 50th (Northumbrian) Division. John Strick was wounded and evacuated by air to North Africa. In October 1943, he re-joined his regiment and took part in the beyond the Volturno and at Monte Canino. He was then placed in charge of a reconnaissance patrol (known as ‘X’ patrol or ‘Battle Patrol) and was again wounded.

On 20 January 1944, he was wounded for the third time and evacuated to hospital. On 10 February 1944, he re-joined the battalion in the Anzio beachhead and eight days later he was killed.

A quotation from a letter written by Major W.E. Brooks, John’s Coy Commander at the time of this death concerned a conversation which took place between them on the morning of his death:

”During our talk, John told me that he did not think that he would survive this action. He said this in a quite natural way and I made some remark to the effect that I was sure he would. In fact, I know he had said the same thing to A Coy Commander before we moved up….”

The last letter which his mother received from him and written in hospital just before he went (subsequent ones were lost) gave a message from Priestley’s play, the Long Mirror’. It was a wonderful last message but, through it, one could read that John sensed that his time here was very nearly up.

A few months before the war started, he joined the London Irish Rifles, a Territorial Battalion of the Royal Ulster Rifles. On the outbreak of war, he got a commission as he was already partly trained in the O.T.C. He edited the Regimental Magazine, ‘The Ordinary Fellow’, from its inception in October 1940 to June 1941. This he did with considerable success and he also got up a Regimental Art Show. “This” he said, was the fulfilment in miniature of two of my ambitions – to edit a paper and run an art exhibition.”

In 1942, he went to Iraq, thence to Egypt and the invasion of Sicily. He took part in this with a badly poisoned thumb and refused to go to hospital until the fighting was over. It must have been a considerable ordeal going into action for the first time with the agony of poisoned thumb to add to it. John was slightly wounded in the temple and was finally evacuated to hospital by air to North Africa.

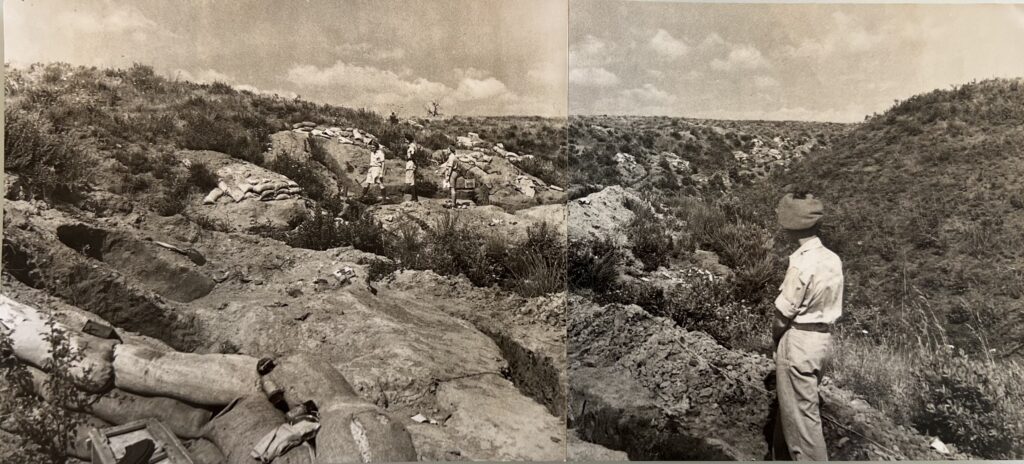

During the Italian campaign, in which he served, we hear very little of his activities until he took over the regimental Battle Patrol of 16 N.C.O.s. Thanks to the MoI articles, we have detailed knowledge of two of these expeditions. The men used to call one stretch of the Garigliano river, ‘”Johnny’s River” because he was so often patrolling its bank or crossing it and leading his men far into enemy territory in order tom locate enemy posts, take prisoners or carry out a fighting patrol.

Always on these patrols – sometimes penetrating deep into enemy territory – John was accompanied by Rifleman Jack Armstrong, his batman and John said that Armstrong saved his life three times. Thus, there existed between an Officer and Man, a much closer affinity than usual.

John was slightly wounded twice on patrol, once by a bullet that lodged in his chest and once when a mine blew up. The shock from this last incident was great, much worse the actual wounds and he was to have gone on to a Convalescent Home from Hospital.

However, he heard that the Battalion had moved to the Anzio Beachhead and he decided to re-join at once though he was far from fit. “They seem to want me,” he wrote of his beloved men. A few days later he was killed instantaneously by a shell. The Coy Commander was badly wounded and the Company Sergeant Major was also killed. For once, Armstrong was not with him as he had been sent to hospital for a few days. Armstrong return to hear that his Captain was dead.

Jack Armstrong wrote a very beautiful letter to his own mother:

“My Dear Mother,

As I sit here and writing you these few lines, I am more than broken hearted. You will and probably will be the same, when you hear the same ghastly new as I heard yesterday on returning from hospital. Captain Strick was killed.

It was the first time I had ever left him whilst we were in battle – a few days before he was killed, he sent me back to hospital because I had a fever and a very high temperature of 102 degrees. When he left him, he shook hands with me and said, “Good luck. Look after yourself.” I told him it was he who needed all the luck. I didn’t know how right I was.

Mother, I don’t know what I shall do now. There just isn’t any future for me. On the three occasions when he was wounded before, I was with him every time. We always said to each other, we were each other’s luck. There was something in that, mother, because we never left each other’s side, no matter how bad the circumstance were.

Everyone in the Battalion liked for his daring and skill and cool courage. If ever anyone deserved a medal, it was him. To think that during the past month, the dangerous corners which the platoon has been in – he always got us out of them and yet when he goes back into a company and was not in what one would call a dangerous corner, he was killed. I might not have mentioned it before but we were in C Company at the time. He had just been out of hospital a week or so after having his last wound attended to.

Yes, Mother, I have lost my best friends – the best in the world. Everywhere he went I was with him. Don’t ever lose that photograph of him – get it enlarged as big as you can so that when the day comes and I will be back again, I shall be able to walk into the house and salute the most gallant soldier and friend I have ever known.

I shall write to his mother as soon as I can. I hope she does not take it took hard.”

Major Lord Stopford, who was acting C.O. of the Battalion when John was killed, wrote:

“I would never have expected John to have been hit by a shell. He was a man for patrol and ambush, direct personal combat with the enemy and very good as it he was. He was an artist at patrol and his men loved him and would go anywhere with him. We, the Battalion and certainly myself personally, will miss him terribly; his studied ‘guerilla-like’ untidiness on patrol, his characteristic accounts of his work, his original views on almost any subject – all irreplaceable. His truly a loss to us all and I believe, that of he had lived, his name would have been know the world over… we all owe debt to him for being himself which we can never betray.”

A brother officer wrote: “He was one of the most courageous fellow I have met – he did not know what fear was.” This is not so. He knew fear only too well at times, but as he himself wrote in a letter: “the fates arrange kindly that, during periods of danger,. My imagination ceases to function. It is only after that one considers that might have happened. Like so many soldiers, I have become fatalistic. It must be so – it be mere accident.”

A brother officer, Captain Mervyn Bonham-Carter (who was killed three weeks later) wrote to his own mother:

“He was such a dear person, a really grand officer – the men loved him and he was a wonderful leader. He had some terrible jobs and always brought them off.”

John’s grave was found but the site is not registered as the ground was extensively fought over and was occupied by the enemy for some time but has now been retaken by our victorious armies.

A young airman said to me: “If only I knew what John meant to do in the future, what line he would have taken in the world. I would dedicated my life to carry it out.”