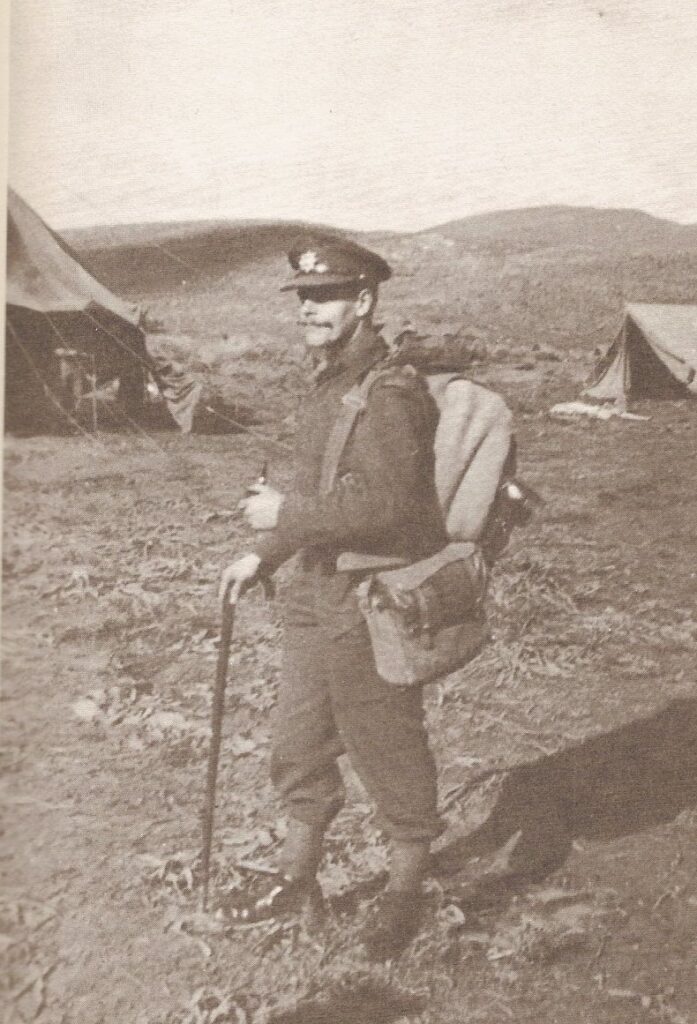

Captain Strome Galloway was part of a draft of Canadian officers who joined the First Army in North Africa in early 1943.

Galloway joined up with the Irish Brigade in February 1943 and along with Captain Gale and Lieutenants La Prairie and Curry took a leading role within the 2nd Battalion, London Irish Rifles (2 LIR) during their period in the line north of Bou Arada.

Captain Galloway kept a diary of the two months he spent with the Irish Brigade and his memories of that time were published in his 1984 book “With the Irish against Rommel“.

As Second in Command of F Company in 2 LIR, he provides a most evocative account of the bitter fighting on 26th February 1943 at Stuka Ridge which we reproduce below.

“Gibbs had instructed Sergeant North to take No 12 Platoon around the hill, past Stuka Farm, to cut off the enemy if they got up to the farm. He was planning to lead the other two platoons in a counter attack. Part of No 11 Platoon was already engaged and the counter attack plan, although gallant enough in its conception, was foolhardy and unsound. It meant all our dug in positions would be abandoned and a melee would be created with the enemy having the advantage of lying down and potting the Irish as they charged forward.

I told Gibbs that I would take over North’s platoon and so North and I raced back to the position on the right and as Gibbs pushed his half awake men into the nullah.

We deployed No 12 Platoon and began climbing the hill and to encircle the farm and converge on the other side with Gibbs’ people in the nullah. We had hardly got up to the crest of the ridge when heavy machine gun fire swept across our attack line, coming from the knoll between F and G Companies, where a section of our Carrier Platoon had been located.

Apparently, they have been overcome as the MG fire was definitely German. We went to ground with the red tracer of the Bosche MGs cutting the air over our heads. I called to the 2” mortar crew to lay a smoke screen on our left front so that we could rush across the plateau and into the safety of Stuka Farm. From there, I hoped to mount an attack against the knoll. The No 2 on the mortar had no bombs! I then detailed Cpl Johnson to work around among some haystacks, availing himself of what cover he could; and from there open up on the knoll to give us some covering fire for the dash to the farm.

Major Colin Gibbs OC F Company

As Johnson began his movement, the Bosche started throwing mortar bombs among our own group and we suffered four men killed and two wounded. The two men I was lying between were both hit and huge chunks of shrapnel whizzed through the air just above me. The enemy MG fire was continuous. Johnson’s people opened up and gave the order to rush the farm which, by this time, I considered to be occupied by the enemy.

Our position just below the crest was untenable now. It was either necessary to retreat down into the night positions where God only knew what situation existed or put on a bold front and assault with the bayonet. I shouted to the survivors to get up and go forward but they hung back. Realising that they were looking to me for leadership, I jumped to my feet, yelling to them to fix bayonets and follow me. Only about twelve answered my wild call. I shouted to them to keep extended and we rushed for the several openings in what we were sure was an enemy held Stuka Farm. As we charged across the flat ground, Johnson’s section, also broke cover and swept in on our left, entering the farm just before we did.

Stuka Farm was not occupied by the enemy, but by three or four members of Company HQ, who normally spent the night there. They were greatly relieved when they saw it was us who were storming the farm and not Germans as they had thought! I detailed my little force of about twenty men to the doors, windows and gaps in the walls; and decided to hold onto the farm until I could ascertain if the enemy were still on the knoll and how I could best attack them. As soon as the Bosche realised we were in possession of the farm, they trained their MGs on the windows and lobbed a few mortar bombs into the courtyard. Everybody was pretty windy.

Stuka Farm, February 1943

Sgt North and I spent more of our time going from post to post joking with the men and keeping them on the alert. To attack the knoll was out of the question, so I decided that the only sound plan was to make a fortress out of our farm and withstand any further enemy attacks. Since the enemy was on higher ground and since, so far as we knew, the other two platoons were liquidated, it would have been suicide to attempt to dislodge them. I decided that counterattack was the problem of the battalion commander, who would call on Brigade for the counterattack force, always held in reserve and centrally located.

Despite the enemy fire, three stretcher bearers, who had been in the farm all along, went out to the crest of the ridge and managed to bring in one lad, who was badly wounded in the shoulder by a mortar fragment. They bandaged him up and I located a bottle of whisky in my quarters and gave him a drink to quieten his nerves. I then replaced the bottle in my kit and went to the wireless truck where Lance Corporal Stratton was attempting to get through to Bttn HQ.

Just before noon, after continuous duelling LMGs and rifles, the Bosche worked around in some low ground and assaulted the farm. The main attack was beaten off, but several of them entered one wing of the courtyard and carried off the three SBs as prisoners, tossing stick grenades into our part of the courtyard. During this assault, the Jerries shouted to one another; but since most of my defences were riflemen in slit trenches within the yard and not right at the gates, we could not see them. Had any of them attempted to rush through the gates, we would have easily shot them down.

Only in one place did I have men positioned right at an open window. This was a Bren post, which shot it out with the knoll. I had just crawled into the room and snuggled up to the wall beside the gun when several rounds came through the window, one of them hitting Rfn FE Janes, the Bren gunner, square in the front of his helmet. He toppled back, his Bren gun clattering to the floor. Fortunately, the bullet failed to pierce his helmet. He got to his feet, removed his helmet, upon which there was a great dent, put it on again back to front, picked up his gun, shoved the muzzle out the window and fired back at his opponent. All this, despite the fact that enemy bullets were continually smashing the window sash and whizzing past his head!

During the morning, the CSM and Lance Corporal Stratton made their way from man to man distributing chocolate bars, hardtack and oranges, which they had found in the cookhouse. This cheered the hungry troops considerably as the morning’s business had cut out all hopes of a proper breakfast. At 1130 am, having got in touch with Bttn HQ by wireless and informing them that we were holding on and giving our scanty information onto the remainder of the company. I detailed a small patrol under Sergeant Udall to leave the farm and work their way around through a gully to the knoll to see what was happening, as the enemy fire had completely stopped.”

“In the afternoon, a platoon of Royal Irish Fusiliers and six Churchill tanks of the Lothian and Border Horse counter attacked towards the knoll. They withdrew again – for what reason, I do not know. It appears that it was the sight of this counter attack coming, which has caused the Bosche to leave the knoll; thus lessening the pressure against us in Stuka Farm. Later, our counter attack force became confused, due to lack of information and the commander, thinking Stuka Farm was in enemy hands, asked Brigade for further orders and was told to attack the farm and pass through and down onto the forward positions.

Rifleman Burton with others on 26th February 1943.

By this time, the enemy was active again and Sergeant Udall, whose small patrol was still in slit trenches outside our “fortress”, risked himself by bringing word across open ground that the counter attack was being launched despite our tenancy of the farm; and that the officer in charge had said it was too late to call off the artillery fire plan. Everything seemed to be complete confusion, except in Stuka Farm. As a result, I got through on the wireless to Brigade and said I was leaving the farm for the cactus patch behind it, not because the enemy was pushing me out, but because our own artillery was going to shell me to cover their counter attack. We then broke cover and dashed across the plateau and down the slight reverse slope into the cactus patch just as the Fusiliers appeared on the scene. This attack swept forward unopposed, moved through the previously overrun forward positions and ‘restored the situation’.

The enemy fled into the wadis on the plain. Our 3 inch mortars got in some fine shooting. Earlier this morning, Corporal Hogan, in an effort to dislodge enemy who were in and around his concealed position, called down fire on his observation post and on himself. In doing so, he had to whisper over the Field Phone in case the Bosche would overhear his orders. As a result, a prong of the enemy attack was broken off just as it was about to launch an assault on Stuka Farm coincident with the one, which we, ourselves, beat off on the other side. Had this pincer movement succeeded, we would have probably lost the farm. Towards evening, our wounded were brought in, as were several German prisoners, one of whom was a sergeant in paratroopers’ uniform and equipment. “Soldat? Unteroffizier?”, I queried him. “Nein, Feldwebel”, he replied arrogantly, pulling down the shoulder of his paratrooper smock to show me his silver haired epaulette.

Several of the Jerries spoke English and they told us that they had been brought from Germany through Italy by train and then flown to Tunisia. The paratroopers were used to “thicken up” the attack. The Feldwebel surrendered by running towards the counter attack holding Schmeisser above his head. He stated that he had seen enough fighting during the war to date and had decided this was a good time to give up!

As darkness fell, Major McCann, Second-in-Command of the Inniskillings, came to the farm to get a report of the action and see what the exact situation was. He brought two more Royal Irish Fusilier platoons, which took up position in front of the farm, but not so far down the slope as the London Irish positions were.

By 730pm, Gibbs came hobbling in, wounded in the leg and Willcocks was carried in with a bad knee wound. A number of F Company, who had been captured during Gibbs’ counterattack at 7am, but released by the Faughs’ counter attack also showed up. So did Lieutenant Wade and ten men of the Carrier Platoon, who had all been scuppered before dawn as the enemy stole up on the knoll. Wade and his men joined us in the cactus patch shortly after the second counter attack had cleared the knoll. By 1130pm, two motor ambulances arrived up behind Stuka Ridge and the wounded were evacuated.

F Company relaxing during March 1943.

Back row: RSM Girvin, Major Dunnill, CSM Jackson, Rfn Burton. Front row: Major Dunnill’s batman, Captain Galloway.

Rifleman Burton, who was Howell’s batman, was getting 11 Platoon’s breakfast ready as the attack developed. He joined me in Stuka Farm about 10 o’clock in the morning and worked like mad all day. Late in the afternoon, he got hold of some compo rations and carrying them across the open to a hut cooked a Dixie full of stew, which he then carried to all the positions in the cactus patch. This, despite the fact that enemy small arms fire was still humming around and numerous mortar bombs were bursting here and there. He also proved himself a wonder at reviving some of the “shell shocked” cases. He merely pummelled them until they came out of their “trance”. Five or six of these lads, who had bolted when we launched our bayonet charge this morning were rooted out of slit trenches towards evening and sent to the farm, all of them scared to death and in a lamentable mental state. Burton’s treatment did a great deal to bring them round.

My own close escapes during the day were many; death and capture were eluded by the narrowest margins. Other than the time when the two lads on either side of me were knocked out just before the bayonet charge and the actual charge itself across open, machine gun swept ground, my two most noteworthy escapes took place very close together.

After giving the wounded chap a swig of whisky in the cook house where he was being attended to by the stretcher bearers, I had barely left the room when three Germans entered with machine pistols and Lugers and kidnapped the three stretcher bearers. Had I been administering the whisky or otherwise off guard when they entered, I would have either been shot in my tracks or made prisoner. According to Rifleman Marchant, my foot was hardly clear of the gap in the wall, which I left by, until the order, “Hander Hach!” was given and they were threatened by three paratroopers. While they were being marched out of the courtyard and down the slope into temporary captivity, I was crossing the adjoining courtyard.

I had just entered the stable where the wireless truck was parked and where I had my headquarters, when a stick grenade came hurtling over the wall and blasted one of my men out of his slit trench. Hearing shouts in German outside the farm, I ran across the next courtyard and had just entered a corner room where Thompson, the company clerk, was keeping watch, when what was probably a German egg grenade came hurtling through the window and exploded on the far wall. The room was filled with flying plaster, clouds of dust and smoke, but no harm was done to either Thompson or myself.

I then rushed back to the wireless truck and tried to silence the dreadful humming sound, as I was afraid that, if the enemy managed to force an entry into the centre courtyard, they would hurl a grenade into the stable to knock out the wireless set, which was giving itself away by its loud humming sound. I frantically pulled wires and turned knobs, but nothing happened; so I jumped out of the back of the truck and underneath it. From this position, I aimed my pistol at the entrance through which the enemy might come – but fortunately none did! I had more ‘wind up’ at this stage than at any other time during the day. I was sure the wireless set’s humming would attract the Germans, who would toss their grenades in to damage the wireless and then follow up with a burst of automatic fire, which would completely finish me off, too!”